Think Before You Speak

Examining the line between free speech and hate speech and how complex the issue can be

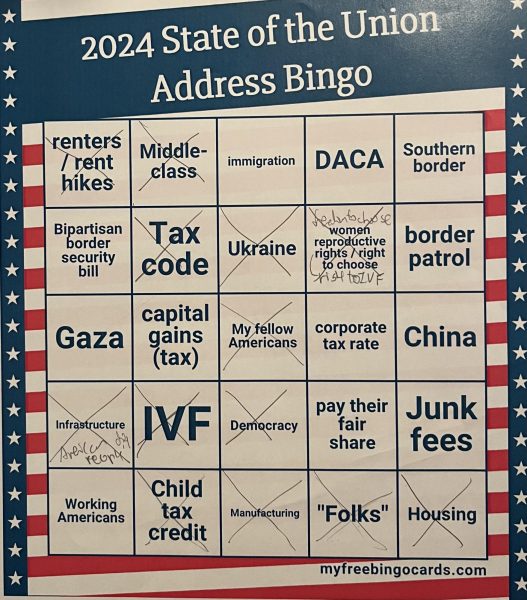

Former President Donald Trump has diminished Black Lives Matter protesters, labeling them as “terrorists” and “thugs.” He has targeted Asian Americans and encouraged hate crimes, calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” and “Kung flu.” Trump has also posted ill-witted claims on public platforms, inciting violence upon Capitol Hill in what many consider “an act of violence.”

Throughout recent years, division and polarization have been inflamed to extreme levels, and the line between hate speech and free speech has been blurred significantly. Despite having a large platform and substantial influence, certain people in power neglect the dire consequences resulting from their unfiltered ideas and feelings. For example, the coronavirus was and still is a hotspot for debate. Numerous prominent politicians have not always supported science amidst the pandemic: former president Mike Pence, Iowa senator Joni Ernst, South Carolina senator Lindsey Graham, and more. This raises one important point of regular debate: is there is a free speech breaking point? Is there a line at which the hateful or controversial nature of speech should cause it to lose constitutional protection under the First Amendment?

Contrary to widely held misimpressions, at present, there is no category of speech known as “hate speech” that is not uniformly prohibited by law. According to the American Library Association (ALA), speech that threatens or incites disorder or that spurs a motive for a criminal act may, in some instances, be punished as part of a hate crime, but not merely as offensive speech. Only when offensive speech creates a hostile work environment or disrupts school classrooms, it may be prohibited. “When I think of the issue of free speech versus hate speech, a dimmed line appears,” explained Zayd Aslam (‘23). “Free speech’s purpose is to protect your opinion, while the purpose of hate speech is to incite detestation.”

The 2020 presidential election was a well-publicized battleground of free speech, hate speech, and misinformation. Political figures like Trump and his former senior advisor Stephen Miller are people with large platforms that have an especially weighty responsibility in drawing this line. For example, the surge in hate incidents after the election wasn’t limited to just hateful words. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a civil liberties group, reported a rise in vandalism and even physical attacks in the immediate aftermath of the election. The New York Police Department (NYPD) reported a huge spike in what they call “bias crimes,” which increased 115 percent between the election and early December 2016. The Chief of Detectives Robert Boyce commented: “The national discourse has effects on hate crimes—hate speech I should say, hate speech.”

With the raised awareness comes increased calls for laws punishing harmful or offensive speech based on gender identity or race. There needs to be a legal principle at which tangible consequences can be set to ensure no future actions repeat the past. The first step is to examine the source that distributes all kinds of information quickly: the social media platforms.

Following Trump’s ban across various communication sites, Facebook has come under more scrutiny for its role in distributing false and divisive information in the previous months. According to the New York Times, Facebook’s employees have different outlooks upon its future. “On one side are idealists, including many rank-and-file workers and some executives, who want to do more to limit misinformation and polarizing content. On the other side are pragmatists who fear those measures could hurt Facebook’s growth, or provoke a political backlash that leads to painful regulation,” Kevin Roose, Mike Isaac, and Sheera Frenkel write.

“There are tensions in virtually every product decision we make, and we’ve developed a companywide framework called ‘Better Decisions’ to ensure we make our decisions accurately and that our goals are directly connected to delivering the best possible experiences for people,” said Joe Osborne, a Facebook spokesman.

Furthermore, Twitch, the live-streaming platform popular among video game players, unveiled new guidelines in December of last year to crack down on hateful conduct and sexual harassment on its site. The site said it had broadened its definition of sexual harassment and separated such violations into a new category for the first time, in order to take more action against them. Under the new guidelines, Twitch will ban inappropriate or repeated comments about anyone’s physical appearance and expressly prohibit the sending of unsolicited links. The company also said it would prohibit streamers from displaying the Confederate battle flag and take more action against those who target someone’s immigration status. Violators could receive warnings, temporary suspensions, or permanent bans from the platform, according to the Social Science Research Council.

“Obviously, it is legal to say hateful things because defamation laws only pertain to whether something is factually correct,” explained Dax Gutekunst (‘23), a twitch-user. “So, sources like social media outlets have to understand how detrimental it actually is. Though the journey is still long, I believe that Twitch’s recent decisions opened up a good discussion on how even words that we use lightly can cause lots harm when used in malicious ways.”

Of course, the implementation of this distinction is not just a simple equation. The freedom of speech is often considered the hallmark of a free society. There is always a difficult question: if we start curtailing speech, where does it end? And perhaps, even more so: is the freedom of speech and limitation of hate speech fundamentally incompatible?

The solution cannot just be black and white. There needs to be careful consideration that comes with even the tiniest guidelines and discourse about how change should be executed.

Crystal Li joined The Tower in her freshman year when she moved from Shanghai to San Diego in 2019. Now a senior, she fondly looks back on the four-year...