Have you ever watched Netflix in bed with subtitles on, turned away from the screen for one second, and questioned if what you heard from the screen was English? Or when watching something without subtitles, rewind three times to finally pick up what someone was saying?

If you have, you are not alone. Our generation has developed a reliance on what was originally created to translate dialogue from a foreign language into the native language of the audience. Subtitles are useful when watching things like Crash Course or Khan Academy, as you could take notes more efficiently; however, when used to watch movies, subtitles are taking away from the art form we tend to forget film is.

Louise Rosenblatt, a university literature professor, distinguished between two different ways people read as part of her “transactional” theory: efferent reading and aesthetic reading. Efferent reading is when you read for a take-away, like reading the instructions on a medication bottle, watching a how-to video, or reading an educational article for homework.

On the other hand, aesthetic reading is an experience with a work of art. Reading your favorite book, watching a play in the theater, and watching a movie. You don’t need to remember all of the specific details. When we watch films, we watch for the experience, to immerse ourselves into the creators’ world. This is why movie theaters don’t have subtitles on the big screen; they can be distracting. The constant wandering of our eyes at the bottom of the screen, reading the script efferently instead of watching the film, robs people of a sensory experience.

As English teacher Dr. Kathleen Kelly explained, “when you go to the theater, no one hands you a copy of the script. No one gives you the book and says, ‘Welcome! Have a seat.’” The theater is a space that allows us to experience a form of storytelling, based on auditory and visual information as opposed to printed text. We immerse ourselves into how the actors and actresses decide to model a story or a character. Theater is an art form similar to films: it’s not efferent.

However, Sapio Research suggested an average of 31% of people would go to more live events and shows if more had captions on a screen in the venue. Among 18 to 25 year olds, that figure was 45%, compared to 16% among people older than 56.

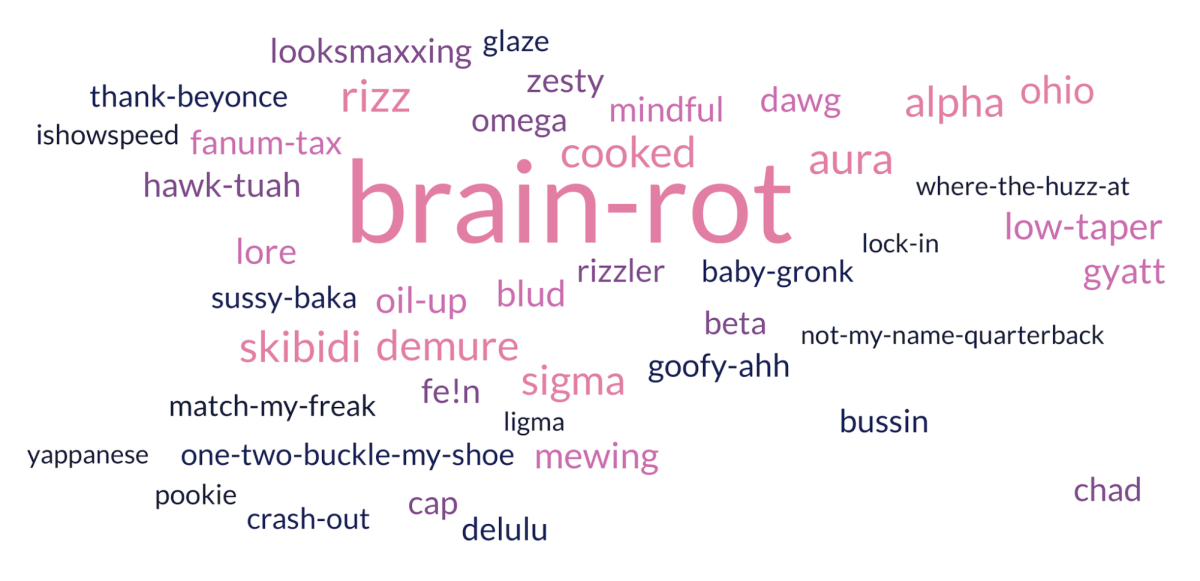

It is just recently that people have started to develop a reliance on subtitles. Techspot.com conducted a survey in 2022 that showed 80% of Gen Z feels they need to use subtitles, and this younger generation was much more likely to use subtitles, compared to the 20-30% usage of the older generations.

This sudden increase in usage has developed from various factors, such as a growing popularity of foreign media and the changes of sound mixing. However, one of the biggest factors is multitasking. Techspot explains that younger viewers like to “quickly read subtitles, glance at what’s happening on the TV, and then resume looking at their phones.”

Amy Yan (‘26) explained, “Sometimes I get really distracted or bored if I’m only listening to the audio because I think I subconsciously filter it out as background noise, so sometimes subtitles can be helpful to provide a visual element that keeps me engaged in whatever I’m watching.” But with subtitles becoming the center of attention instead of the film, it feels like something is missing without them.

The American Association for the Advancement of Science explained that the brain can’t effectively handle more than two complex, related activities at once. When a movie is playing with subtitles, your brain is processing two things simultaneously: reading the subtitles, and immersing yourself into the movie. Your brain will always prioritize the subtitles, and if there are words flowing at the bottom of the screen, your eyes will automatically read along with it. This is why the visual element becomes the subtitles instead of the movie, because your brain simply can’t prioritize both.

Sapio research explained that another reason could be because there is far more acceptance of subtitles by young people because it’s the norm. Part of it is that people in the younger generations grew up watching videos on social media, where subtitles are the algorithmically encouraged default. When you train your brain to watch videos with subtitles constantly, it will be hard to take it away. And this is the problem.

When we watch films with subtitles, our eyes will automatically flick towards the bottom of the screen when we don’t understand something. Dr. Kelly explained, “[Subtitles] get in the way of our engagement with a work of art.” Instead of watching, people are reading.

She added that sometimes her classes watch scenes from Shakespearean plays with subtitles, when it is hard to understand what the actors are saying. Dr. Kelly said, “students have asked me to turn on subtitles…of course I say yes. But I wonder if it’s the same experience of a play if they were to just watch it instead of read it.”

Sometimes we don’t need to understand every word a person says. We watch movies and go to the theater for the experience. Taking away subtitles could help immerse readers into the way talented actors convey the story, and bring you into the film rather than stepping away from it and trying to understand it word for word.

Yes, the language in Shakespeare’s plays is often difficult to comprehend, but watching the actors’ faces and interpretations could be just as, if not more, beneficial to helping you understand the work.

Next time you watch a movie, try to fully immerse yourself into the film. One unclear name or word doesn’t matter, and noticing the characters emotions yourself instead of reading a *sighs heavily* on the bottom of the screen could be worth a try.