Writer’s block. It’s my academic nemesis. When I experience the block while writing an essay or research paper, I flounder in a limbo between thoughts and words on a page. Yet, breaking through that wall triumphs over any frustration.

This year, in response to the prominence of Artificial Intelligence (AI), many English teachers replaced processed essays with timed ones on Exam.net, a software that facilitates in-class timed writings and prevents AI usage. The History and Social Sciences Department took similar actions, using Exam.net for smaller essay assessments and rethinking the traditional processed research paper — a curriculum staple. According to both History and Social Sciences Department Chair Ms. Karri Woods and English Department Chair Dr. Anna Clark, these changes are not final and the departments are still in the process of determining how to move forward.

Timed writings assess students’ abilities to formulate a claim and support it, while preventing AI-usage. Abandoning processed essays doesn’t seem too detrimental when we view writing from an assessment perspective. But what do we lose?

As a senior who has been through seven years of the Bishop’s writing program, I implore Bishop’s to maintain processed writing in its curriculum. Teachers are still deliberating the timed writing question. “When we use Exam.net, it is only because it seems like the best of a bunch of sub-par options,” Dr. Clark said.

However, is shifting to timed writing worth sacrificing other intellectual benefits that require time to develop? Writing is one of the most profound forms of expression; it is a reflection of the past, a portrait of the present, and contemplation of the future.

Timed writings are simply not adequate.

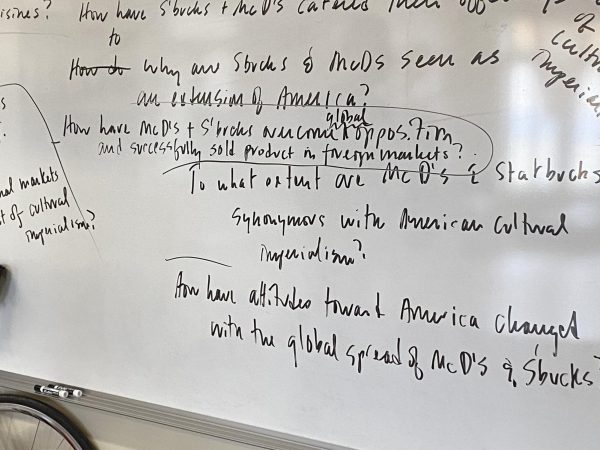

The research paper I wrote in former history teacher Mr. John Nagler’s Honors United States History class is a good example. My topic was the impact of American franchises, including McDonalds and Starbucks, as a form of cultural imperialism abroad. I remember this paper because I struggled — a lot. It was difficult articulating a specific thesis, and the structure drove me crazy. It took me a long time — quick milk break brainstorm sessions with Mr. Nagler, hours staring at my notecards, and days rearranging my outline. This process pushed me as a writer and thinker. However, if I were to be asked to do that in a timed setting, I would not be able to sit in that challenge and grow.

History and Social Sciences Department Chair Ms. Karri Woods described the research paper as a cornerstone of the Bishop’s History and Social Sciences Curriculum for decades. This semester, the department is “piloting a multi-day, in-class model instead. Students still evaluate and connect sources but will write in class to ensure authentic engagement.” However, I would hate to see the traditional research paper — a fundamental piece of my growth as an analytical writer — transform due to AI.

Voice and style are some of the most recognizable criteria in a Bishop’s essay rubric. In the early days of my Bishop’s career, this confused many of my peers — myself included. Many wondered: “Why does voice matter?” But as I grappled with this concept through numerous revisions, and through playing with word choice and syntax, I eventually grew my own writing identity.

Timed writing does not offer that opportunity.

Under a time constraint, students are forced to prioritize ideas over the methods they choose to use to express those ideas. While critical thinking and argumentation are valuable, developing a writing style (whether you prefer em-dashes, wielding sentence length, etc.) is just as important. It is a differentiating factor between a good paper and a great one.

When we examine great authors, their success emerges from their voice. They engage the reader not just via content, but by how they communicate. In English Teacher Dr. Clara Boyle’s Advanced Honors English class this year, we read excerpts from The Writing Life by Alexander Chee. Chee’s content was engaging — but it was his voice and style that amplified his messages about identity and belonging.

In History Teacher Mr. Matthew Valji’s Honors Atomic Bomb class, we read several texts, including The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes and The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg. These books, which unpacked the scientific development of nuclear weapons and Cold War era tensions surrounding their use, respectively, were digestible because of style. Both Rhodes and Ellsberg could have chosen to just communicate the same message with straight facts, without using their voice to weave a narrative. But it is their abilities as writers and storytellers that elevates their discussions of topics that have been expounded upon many times.

AI, too, hinders this development. “I do think that [AI’s] use in school imperils students’ ability to develop their own style” among other things, Dr. Clark expressed. I agree with this sentiment. However, I question that timed writing is a solution that reverses this effect.

For Advanced Honors English student Selene Wang (’25), processed writing improved the quality of her work. “[It] has allowed me to shape my voice and style,” she said.

The writing process itself is invaluable to a student. This includes having time to brainstorm, form a thesis, search for evidence, consider structure, and modify. Timed writing removes these aspects entirely.

As Olivia Henderson wrote in an article arguing against timed writings for the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center at UCSB, “prioritizing speed positions the university as a center for training productive workers at the expense of its potential to develop insightful, nuanced thinkers.

Ultimately, timed writing utilizes a different skill set. Processed and timed writing are not one-to-one substitutions. Per Arthur Lau in Inquires Journal, Dr. Brenda Rinard, a member of the University Writing Program at UC Davis, asserted that “timed writing on standardized examinations constitutes a distinct ‘assessment genre’ with its own unique rhetorical situation.” Skills exercised in timed writing, thus, may not be widely “generalizable.”

I attribute the process of thinking, brainstorming, drafting, and revising as most beneficial to my development as a writer. If that opportunity had not been available, I would probably not be writing this article. Additionally, as a Tower editor for three years, I’ve seen the power of this process transform drafts. I’ve seen writers grow into their own, as they learn to incorporate feedback and revise. The process is as essential to journalism as it is in any other class.

An aspect of the process is writer’s block, which is less effective in a timed setting. Though detested, writer’s block is a signal that you are grappling with often difficult themes or concepts. It means that you are reaching for an understanding or perspective that is beyond the surface.

However, oftentimes in timed writing, the smartest course of action is to move on when unable to articulate an idea, or when your argument just isn’t coming together, thus losing the struggle that is so essential to writing.

Writer’s block can also cause the brain to shut down, thus leaving the student either unable to write or brain dumping whatever comes to mind. Writing is not inherently a painful process (unless you truly hate it), but feeling lost or inarticulate — and working through those states — is why writing matters. Chances are if you are able to write everything without this struggle you are either a generational talent or thinking in generalities. It’s most likely the latter.

Lastly, an aspect of the writing process also includes the ability to take risks. Taking risks does not just include voice and style, but form and argumentation. In a timed setting, some students can feel more inclined to stick with a concept that is easier to prove, basic even, in order to obtain a better grade. Risk is discouraged. Selene agreed with this sentiment. “I am less inclined to take risks during timed writing because I have to stick to the first argument I come up with in order to have finished essay by the end of the period,” she said, “There is no time to scrap a bad first paragraph and start over with a fresher, potentially better argument.”

In Advanced Honors English, I wrote an essay that put the plays Hamlet and Arcadia into conversation. We were free to determine the best form for this conversation, whether a traditional essay or a conversation between characters of the plays. I chose a series of short talks. I admit that I was hesitant at first. A traditional essay would be safe and straightforward. With the encouragement of Dr. Boyle and the extra time to parse out how I would break the traditional essay form, I was able to produce something different that blended personal narrative, creative writing, and analysis. This essay took me several weeks of thinking and drafting — and even after all of that I am still going to revise. There is no way I would or could try this new form in a timed setting.

Writing is important because of its exploratory nature. Students create and meditate on topics in their voice. If that trait is stifled by timed writing, I predict a decline in the quality of student writing. Timed writing feels like a test. On the other hand, the writing process ultimately encourages students to think and grow, along with being assessed.

Resorting to AI, though, is not a better option. “I have seen the depth, quality, and polish of all professional, scholastic, and academic writing begin to decline, and I suspect AI to be one of the culprits,” Dr. Clark said. However, again, leaving processed writing behind is not effective when both timed writing and AI hinder exploration in writing.

Curricular change is inevitable in response to a developing AI landscape, and, currently, timed writing is supposed to lend to our evolution as writers. For now, this seems satisfactory. Yet, note that the current high school student body is one that has done processed writing for the majority of their academic career, thus developing their writing styles and fundamental skills. As Ms. Woods shared, most of the seniors she teaches are able to produce great essays considering the time constraints (though grading criteria and expectations are relaxed with timed writings). The effects of this change on long-term student development, such as my sister who will enter ninth grade and subsequent classes, could be much more detrimental, removing the freedom for discovery and articulation.

The abilities to persevere through writer’s block, to be creative, and to effectively communicate are absolutely essential. Some semblance of processed writing must be kept in the curriculum — for the growth and intellectual development of the next generation of leaders and thinkers.