In 2025, the U.S. News & World Report ranked Princeton University as the #1 National University in the U.S., University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) as #15, and Rice University as #18.

In the same year, Niche College Rankings ranked Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as the #1 College in the U.S., UCLA as #20, and Rice University as #8.

Published annually by such popular websites, these rankings have long been known for listing the top schools in the country. Yet, like the discrepancies between these two lists, the numbers in college rankings can be misleading, offering only a glimpse into each college’s full story.

How Colleges Are Ranked

“I think a lot of people will be surprised if they went into U.S. News and really broke down what the rankings were based on,” Director of College Counseling Ms. Wendy Chang said. “It’s very frustrating as a college counselor when students and families are so driven by the rankings, but they do not bother to look at what goes into determining them.”

Most ranking websites list their criteria and express the weight of each one through a percentage. For example, U.S. News weighs “first-year retention rates” as 5%, while Forbes prioritizes weighing “three-year average retention rates” at 10%. Although every database prioritizes different conditions, they all similarly focus on endpoints — statistics regarding debt, graduation rates, and retention rates are emphasized over measuring the student experience.

There are various layers in assessing these determining factors. First, spotlighting output measures takes away from what the Bishop’s college counselors call the most important aspect of considering colleges: making sure it is the best fit for the student. As Associate Director of College Counseling Ms. Marsha Setzer said, “our brain wants to simplify things, but understanding a college community and what it has to offer can never be drilled down to a number.” Graduation rates and faculty salaries of a school say little about how happy a student will be there.

Second, these numbers lack context. For example, when considering the 8% weight of “faculty salaries” in the U.S. News rankings, it’s hard to infer whether this measures faculty satisfaction with salary or actual salary levels. Deep in their website, U.S. News states that “faculty salaries” really assesses “the average salaries for full-time instructional faculty,” and that “salary data was adjusted for regional differences.” The names of certain criteria don’t fully capture what they measure.

Third, Ms. Chang explained that these rankings are often arbitrary and subjective. For example, U.S. News weighs “peer assessment” as 20% of their ranking criteria. That means 20% of an institution’s ranking is based on how other colleges perceive them.

When Ms. Chang worked as an admissions officer at Harvard University, she was responsible for completing the University’s ranking surveys. She described that the president of a very small college in New Jersey was good at making hot sauce, so “he would send gifts of hot sauce to other college presidents to try to promote his school to them.”

Clearly, although a large part of the ranking process is subjective, some colleges manipulate the measurable factors to their advantage.

Gaming the College-Ranking System

According to reporting in Boston Magazine, “schools ranked highly on well-regarded websites receive increased visibility and prestige, stronger applicants, more alumni giving, and, most importantly, greater revenue potential…a low rank leaves a university scrambling for money.”

Boston Magazine’s article, “How Northeastern University Gamed the College Rankings,” explained that this desire for prestige and revenue potential was what drove Northeastern University to manipulate the ranking system in the early 2000s. Northeastern’s U.S. News ranking climbed 40 places from 2005 to 2010. In an interview with Boston Magazine, Richard M. Freeland, the President of Northeastern from 1996 to 2006, stated, “We had to get into the top 100. That was a life-or-death matter for Northeastern.”

The article described that Northeastern met annually to calculate what specific actions could make their ranking improve, focusing on a switch to the Common Application. Northeastern knew that the Common Application would make it easier for students to apply, and if more students applied, more students could be turned away — lowering their acceptance rate and making the school appear more selective. In 2006, after this transition, Northeastern went up seven places in the rankings — a 12% rise.

Northeastern was not alone in this endeavor. Boston Magazine reported that in 2008, Baylor University incentivized newly admitted students to retake their SATs, offering a $300 campus-bookstore credit for simply retaking it and $1,000 yearly in student aid if their scores improved by over 50 points. While Baylor tried to manipulate their ranking through test retakes, The New York Times reported that in 2011, Iona College completely misreported SAT test scores, alongside “graduation rates, freshman retention, student-faculty ratio, acceptance rates and alumni giving.” The New York Times also found that Claremont McKenna College had been misreporting SAT scores, and in 2012, Vice President and Dean of Admissions Richard C. Vos, “resigned after admitting that he had inflated the average SAT scores given to U.S. News since 2005.”

Boston Magazine further reported that in 2012, George Washington University acknowledged that they had overstated the percentage of students who graduated at the top of their high school classes, and Emory University also admitted to misreporting GPAs for four years and SAT scores for nearly twelve.

This manipulation prompted Reed College to opt out of the ranking system. In 1995, President of Reed, Steven Koblik, told U.S. News that he didn’t find their ranking system credible. “Reed’s decision won praise from professors and administrators…many of whom had witnessed the pernicious effects of the rankings,” their website states. According to a 2012 survey of admissions officers conducted by Inside Higher Ed, only 3% of college admission directors believed that the title “America’s Best Colleges” was accurate, and just 2% thought that ranking systems were “effective at helping prospective students find a good fit.”

The following year, U.S. News placed Reed in the lowest tier of their rankings list.

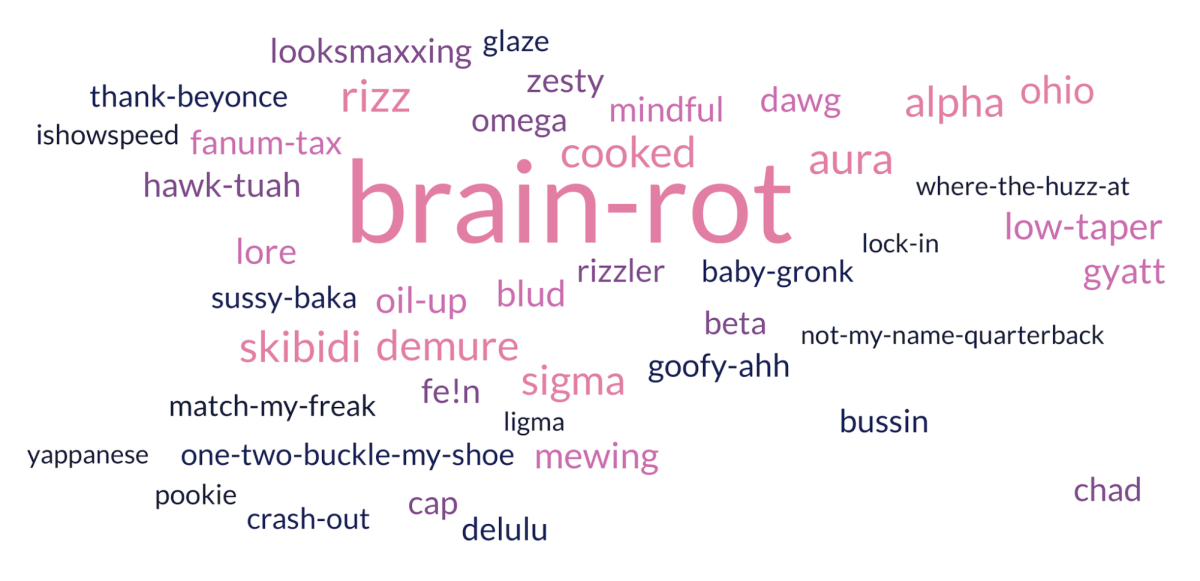

It is important to note what goes into college rankings, and look beyond the curtain of prestige. As a senior that has just experienced the college application process, Angelina Kim (‘25) noted, “Every ranking system has their own unique ranking equation that weighs some factors more than others, so it’s not reliable unless they properly explain what they prioritized more.”

What School Rankings Don’t Tell You

School rankings often exclude pieces of the puzzle that aren’t captured in numeric form. “Rankings are simply numbers,” Angelina explained.

Ms. Haddad gave the example of considering the location of the school — a student may want to go to Columbia University, an Ivy League school, for its academic rigor. However, the same student may also dislike large cities. “And then they tell me, ‘I think Columbia is the best fit for me because of the rankings.’ Well, there’s a lot more there that we have to unpack. Because it might not be the best fit for you,” Ms. Haddad explained. If a student likes many elements of the school, the job of the college counselors is to help the student extrapolate.

Tyler explained, “if I enjoy city life then I would not want to go to Cornell because it is geographically isolating. If I truly benefit from teacher-student interactions and smaller class sizes, then UCLA may not be the best fit, given its 100 to 400 student class size.”

Naveen Hernandez (‘26), who is interested in theater and science, said, “MIT is rated higher than UCLA, but MIT does not have a robust theater program, so I would be less inclined to go there. Similarly, I wouldn’t apply to somewhere like Julliard because it doesn’t have good science programs.”

As Selene explained, “If a school is in the top 50, or top 20, chances are it will give you a good education no matter what major you go into. However, rankings will tell you little to nothing about how you would fit in the school environment, whether you would enjoy going there, or anything about your long-term success in life if you happen to attend that school.”

Current perceptions of college rankings at Bishop’s

“Bishop’s is a place where everyone is striving to be the best in their field. We see college rankings as a measurement of that achievement; in other words, going to a higher ranked college is seen as a greater ‘achievement,’” Naveen explained.

In this high-achieving environment, Angelina said, “a college application feels like an accumulation of all the years we studied at Bishop’s. It’s almost like our college results are being used to either validate or discredit all the hard work we’ve put into the past few years.”

Naveen and Angelina both used the word “stressful” to describe the general culture of college rankings at Bishop’s. Naveen said, “hearing everyone around you applying to the same [top colleges], combined with the media feeding you information that ‘Oh, you are not enough, take my $500 essay writing course’ can be really stressful. Ultimately, I think the environment I’ve been fostered in promotes focusing on college rankings as I apply.”

Students in lower grade levels share the same sentiment. Elliot Armstrong (‘29), still in middle school but with a brother who is a senior, explained, “My parents and friends talk about certain colleges being better than others…I believe going to a highly ranked school will really help because each and every thing at a highly ranked school will set you up for your future, and help you reach your goals a lot faster.”

The sentiment that higher-ranked schools will bring more opportunities is especially prevalent. Eeshan Ramkumar (‘30) said, “a highly ranked college is important because they will have the best teachers and facilities. I assume that the people there are really smart as well as the teachers.” Nico Bravo (‘28) explained, “I assume [higher ranked colleges] have more opportunities and resources to support my growth into a mostly functional, independent individual.”

Furthermore, Abigail Guo (‘28) noted that the choice between going to a lower-ranked school that fits her interests and a highly ranked one that doesn’t would be a really difficult decision. “If I go to a lower-ranked school that fits my interests, one, my parents wouldn’t be too happy, and two, I’d feel less worthy than students that chose highly-ranked schools. If I go to the highly-ranked school that doesn’t fit my interests, I would regret throwing away my passion and feel sad for giving up on something I loved so much. There’s no right answer.”

Whether it’s seniors, juniors, underclassmen, or even middle schoolers, college rankings are engraved into our community. Ms. Setzer explained that changing this sentiment would be a huge culture shift at a competitive school like Bishop’s. “[Students are] initially familiar with a certain number of schools because they’re more popular, they’re more well known, and they have higher name recognition,” Ms. Haddad added.

Aska Enomoto (‘28) explained this phenomenon of name recognition. iPhones and Androids have similar technology, but many value the former more. Similarly, “blue text bubbles are just better compared to green text bubbles, even though now they both do the same thing,” she explained.

Thus, as Ms. Setzer said, “When we’re having these conversations, we are pushing against so much information that students already bring to the table. We don’t meet with students until they’re almost halfway done with high school.”

Angelina attested to this fact, explaining that, “as an underclassman, I didn’t know many colleges in the first place, except for the top schools that were frequently mentioned in common media. However, I ended up removing many of those schools from my personal ranking as I went through the college application process because they didn’t fit my personality or share the same interests.”

Ms. Haddad added that by the time seniors get to the end of their college-application process, the ranking and prestige of the school is never the sole factor. Students have often picked a lower-ranked school out of the schools they were accepted to because of personal fit, and ended up enjoying their college experience just the same.

Tyler concluded, “It is not the name of the college but how the student utilizes the resources at the college that will bring more opportunities later on. Every college is going to give you a good education if you utilize it to the best of your ability.”

![Leia (‘30) and Sara Park (‘32) ended their combative performance with a yell known as a kiyap. Leia explained with a proud smile, “I realized this when I was little, but not many people see taekwondo every day. For me, it’s a daily occurrence, so it feels very normal…when I do [a performance] in public, everyone’s like ‘Wow, that’s really cool’. So it always reminds me how this isn’t a normal thing in other people’s lives and I think it’s really cool that I can share that.”](https://thebishopstower.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-02-at-2.07.47-PM.png)