Emma Donnelly (‘25) did not know she needed help. Throughout the beginning of high school, she attained strong grades and never had many issues academically. Then tenth grade math hit. She still did not struggle with the concepts, but instead found herself needing more time on each question.

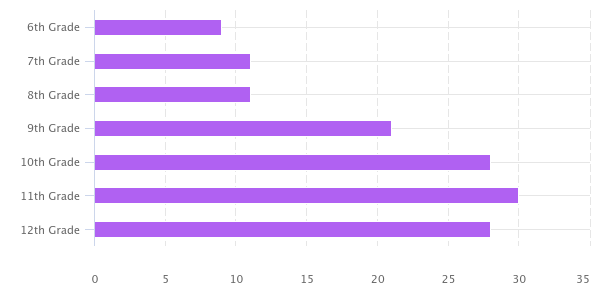

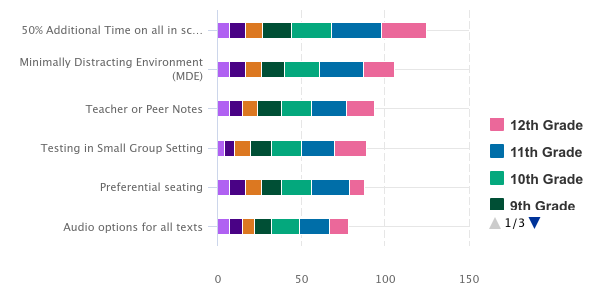

In recent years, learning accommodations seem to have become more prevalent on campus. According to Director of Teaching and Learning Dr. Stephanie Ramos, 135 students, which amounts to 16% of the student body, have learning profiles, which detail a student’s learning strengths and challenges — and oftentimes include learning accommodations, such as extended time or small-group testing. In 2019-20, the Learning Center, led by former Director Mr. Ken Chep, anticipated that 54 students, grades 7-12, would need accommodations the coming year.

Why the Rise?

Clinical Psychologist Dr. Amy Ellis — who runs private practice Learning Development Services in Claremont, San Diego — theorized that this rise is largely due to the lessened stigma. “It’s more accepted to be able to talk about it,” Dr. Ellis explained, “Whereas in the past, people tended to be more private about it or unaware of possibilities or accommodations and services in schools.” 5% of Dr. Ellis’ clientele are from Bishop’s, and she has been in practice for 30 years.

This acceptance is exactly what contributed to Alexander “AJ” Gwanthey’s (‘25) decision to get tested the summer before senior year. “I was just kind of skeptical at first…I didn’t know if I was just dealing with normal people things or if there was actually something wrong with my brain,” he said. AJ recalled that during a timed English assessment, he and a friend were both taking a long time to finish. His friend, who had extended time, asked whether AJ also had it. That was when AJ started wondering if he should get tested. “As I started to see people that I know having extra time…I related more with people who had extra time,” he said.

It’s a positive feedback loop. As more students become open to testing, diagnosis, and learning accommodations, other students see increased acceptance, leading to an increased willingness to go get tested.

Dr. Ramos believes that this shift in culture regarding well-being, mental health, and neurodiversity came after COVID-19. “There had been a significant increase prior to COVID-19, but the pandemic exacerbated the issue and brought more awareness to these kinds of challenges” with “increases in [the] prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of learning and mental health challenges,” Dr. Ramos said. This shift shaped Bishop’s overall school policy, which has emphasized well-being through hiring an additional learning specialist and counselor, changing the Dean of Students role, and creating an advisory health curriculum.

Whereas before Dr. Ramos, the Learning Center primarily dealt with students who had learning disabilities or accommodations, now the Center offers academic and study skills coaching to all students: from 2022-2024, just over 50% of the student body engaged with the Learning Center at least once.

The Impact of Learning Accommodations’ Rise

Learning accommodations have been transformative for those who went through the process to get support. By working with the Learning Center and being supported with accommodations, Laine Jeffrey (‘25) was able to learn more about herself as a student. “The process was…definitely long and hard, but it’s seriously helped me so much,” Laine said. After looking through her transcripts, not only did she notice a “serious and drastic increase” in her grades, performance, and comfortability taking tests, but that she had “become a better test taker and…learned so many different testing and study habits.” Laine realized that she tests better in a small environment or by herself. At times, Laine also has used the Learning Center to proctor her tests.

Proctoring tests is just one facet of the center’s work, and, according to Dr. Ramos, teachers have always had to share the burden. However, the rise in students with learning accommodations has led to some contention around who is responsible for test proctoring, as some teachers feel that it is primarily the Learning Center’s responsibility. “In my mind, the learning center should take care of all the extended time scheduling,” English teacher Ms. Amy Allen said.

But, the Learning Center does not have the space to proctor all assessments for all students with learning accommodations. “We don’t have the physical space, but we also don’t have the manpower. So if I had a student testing in here with me, I couldn’t work with another student,” Dr. Ramos said. The rise in students with learning accommodations or even just in need of support has led the Center to be increasingly overloaded.

This overload in the Center has had a noticeable effect on students with accommodations. In the beginning of the year, following her normal procedure, Lanie emailed the Learning Center a week in advance to see if they would be able to proctor her Psychology test with accommodations in the beginning of the year. To her surprise, she got an email back, which she summarized as saying, “The Learning Center was too busy.” This happened a few more times, though Laine admits that she did email on shorter notice for those instances. “It’s definitely a lot more crowded,” she said, “I’ve never experienced that — where it was too busy to take a test. So that makes me also question, like, what’s happening?”

Students with other learning accommodations such as small-group testing or a Minimally Distracting Environment (MDE) are also impacted. “It got so packed that we didn’t have the space. So, we reinforced the idea that a small group setting is really like under 20, in which case all Bishop’s classes or most are small groups,” Dr. Ramos said. This year, students were reminded to go to classrooms and only those who need a one-to-one testing environment would continue to take tests in the Learning Center.

A Game of Scheduling Tetris

To mitigate this overcrowding, according to Dr. Ramos, the Learning Center reminded teachers in an email to coordinate testing with students’ schedules, rather than asking the Learning Center to proctor.

However, some teachers interpreted the email as a policy shift. One teacher explained their understanding of the email. “They are maxed out in terms of personnel, time, and space, and so they tell teachers in their email that we need to proctor our own student extra time, and they lay out specific expectations for doing so which are quite detailed. They also suggest that we give up a prep period each week to help with the extra-time testing,” they said. This email was part of internal faculty communication, and the teacher requested anonymity in sharing this dissenting perspective due to fear of retaliation.

The Tower spoke with numerous teachers both on- and off-the-record across all departments about their experience accommodating test takers. While classroom ratios of students with accommodations and without vary from teacher to teacher, ten teachers across various departments observed a noticeable increase in student accommodations. For some, their experience felt like it exceeded the 16% overarching statistic.

When told of this fact, Ms. Allen reacted with “I don’t buy that.” Across her regular-level English classes, 47% of her students have learning accommodations. In Ms. Allen’s honors classes, though, that number is much less with only three students across three sections. Due to the English Department’s shift towards timed rather than processed writing assessments, the topic of extended time and learning accommodations has become increasingly relevant. In two other teacher’s classes, just under half of their students have learning profiles.

The unequal distribution amongst classes can make these accommodations feel particularly overwhelming in specific classes or for specific teachers. Teachers and students with learning accommodations are responsible for coordinating extended timed assessments, requiring students to take initiative and “use their executive functioning skills,” said Dr. Ramos.

“It’s a logistical nightmare,” said Ms. Allen.

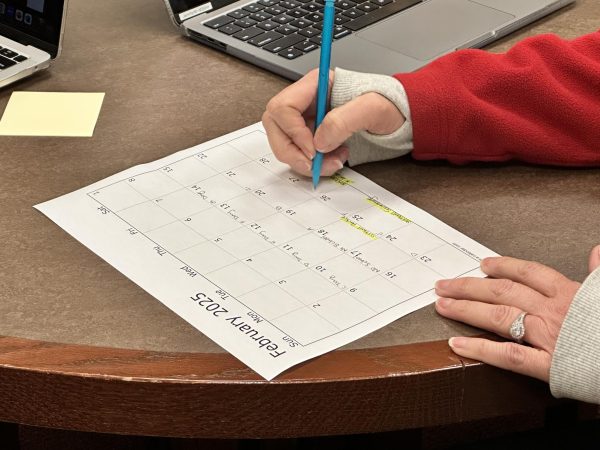

Many Bishop’s students have busy schedules both academically and extracurricularly, whether it is a sports practice that starts at 3:30 p.m. or five other classes to manage and study for. This makes it tricky for teachers and students with extended time to coordinate a time to finish an assessment where both are available. “Some students are great at making plans. Others are not,” Math Teacher Dolores Williamson said.

Mr. Juan Vidal, a new math teacher, noted that 22% of his students across levels use accommodations, while that number is 30% for his on-level classes. He often runs into scheduling conflicts. “When do I proctor them so that they don’t cheat? When am I available? When are they available? Because I know kids have a bunch of activities. That’s the struggle that I’ve encountered here,” he said.

“It’s not perfect. Our schedule is not built to accommodate long testing periods, and I don’t even know if testing for such long periods is right for well-being,” said Dr. Ramos, “I don’t know if there’s a better way.” While the 2024 first semester cumulative schedule allocated a slot for extended time, the regular A through G day cycle does not.

This year, in Math Teacher Ms. Dominique Voso’s Precalculus classes, 31% of her on-level students use learning accommodations. She shared that the biggest challenge for her is also coordinating with students to use extended time outside of class. “Some of these students don’t have free periods, and coordinating with nine students to proctor extra time is not an easy task,” she said, “It is also challenging to preserve the integrity of the test when students are taking half of the test and then coming back later to finish it.”

This dilemma has led some teachers to modify how they approach test-making and classroom organization. “Now, I try to give quizzes that are 45 minutes long, so everyone can finish during the class period,” Ms. Voso said. Ms. Williamson also has changed how she partitions her lesson plans. “When I have a quiz, I try not to have a lesson after, so students with extended time can finish their quiz in my classroom within the period,” she said.

Last semester, test length was considered during cumulatives. Science Teacher Dr. Anthony Pelletier noted that teachers were told that “the non-extended time students had to stop at 70 minutes or 60 minutes, and then we could go to 100 for the extended time.” For extended time students who had multiple tests per day, this would mean two 150 minute tests in a row or five straight hours of testing.

Students, too, have needed to find ways to fit in their extended time when their schedules don’t match with their teachers. “I wouldn’t say it’s a lack of support. It’s just like there’s kind of a lack of options…for how to incorporate [extra time] unless you have a lot of free periods,” Emma said.

For Brad Ladrido (‘26), sometimes his teachers will have the same free period as him. At other times this is not the case. “I’ll have to go to school at like 7:15 a.m. to start my tests and then email my advisor saying I’ll have to miss advisory just to start my test early,” Brad said.

Emma found that some of her teachers had different policies regarding extended time. During the regular school day, some teachers allowed her to break the test up into sections, while others required her to do the full test in one sitting. This year’s cumulative block schedule, however, standardized this. “Due to the specific requirements for each teacher, I found that having the extra time built into the cumulative block makes it so easy to just sit through the whole length of the period,” she said.

The Stamp of Approval: How Students Qualify for Accommodations

But how would one qualify for these accommodations? Many students, such as Emma, decide to get tested. When she got back her results from her psychiatrist, she was surprised. At first, she was fearful. “It’s just hard to come to the realization that I might actually have something, quote unquote, ‘wrong with me,’” she said.

When students suspect they may need a learning accommodation, many go through an, on average, 8 to 10 hour process of interviews, testing, and data collection and analysis to determine a diagnosis, according to Dr. Ellis. The actual testing process is four to five hours and consists of a variety of IQ, academic achievement, and neuropsychological tests. Though individual clinicians’ practices may vary, Dr. Ellis says that most diagnoses are data-driven. After analyzing academic records and interviews with the students, parents, and, at times, teachers, the students’ tests are compared to data collected over the years.

The testing process is very much objective, not subjective, according to Dr. Ellis. “All the IQ testing and the academic achievement tests are both statistically oriented,” she said, “the students have to meet a certain criteria of one-and-a-half standard deviations difference in point spread in order to have clinical significance and be able to have access to accommodations.”

The tests cover many bases, ranging from ones focused on memorization, to academic achievement, to brain games. When Brad got tested, he went through a series of these tests. One tested him on his focus, requiring him to press the spacebar whenever a screen lit up with a green screen and refrain from pressing it when a red screen showed. He distinctly remembers a drawing test, which tested his ability to recall an image his doctor gave him and redraw it. “Honestly, the tests were pretty tedious. They were like a lot of questions and I felt like part of the test was seeing how long you could keep doing the tests before you started losing your attention” he said.

These tests look for a functional impairment, which leads to suggested accommodations.. This is not the same as a diagnosis, which may not necessarily lead to accommodations. There are over 100 different functional impairments that can be determined from the tests, including visual processing, visual spatial processing, and auditory processing disorder, according to Dr. Ellis. However, the DSM5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition) is the standard book that allows clinicians to determine diagnoses, such as ADHD, Dyslexia, or Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

After this process, clinicians send a report with the data and, if needed, suggested accommodations to Dr. Ramos and the Learning Center. From there, the Learning Center creates a learning profile and discerns whether students will be able to use those accommodations at Bishop’s. “It has to be based on the documentation…[learning accommodations are] not something we can arbitrarily give someone,” said Dr. Ramos.

Is There a Solution?

Dr. Ramos acknowledged the difficulty of scheduling: “It’s hard. It requires a lot of advance planning. One of the reasons that we added advance notice into the homework policy is so that all students would look ahead,” she said. The system currently relies on student accountability and communication; and, now, with the Homework Policy (an aspect of which asks teachers to post homework assignments and assessments a cycle in advance) instituted this year, planning in advance has theoretically become easier.

“We really have to just work as helpfully as possible with the time constraints that were given,” said Dr. Ramos.

Ms. Voso proposed another potential solution. “With the rise of students with accommodations, there is a real need to have a dedicated place on campus with a proctor for students taking tests during or after school,” she said. As someone located in Wheeler Bailey — a space shared by six different teachers, it can get quite “chaotic,” making it hard for students to continue testing, according to Ms. Voso. This would not only make scheduling easier, but allow students to always have a space to continue their testing.

Mr. Vidal, as well, found that, at his old school, a designated proctoring room made testing much more convenient. “Students could just come in to take a test whenever they’re free. I didn’t have to be free for them. There was a teacher there every single period to give the test and read the directions,” he said.

The increase has changed the culture of learning disabilities at Bishop’s. “The community environment now is more open and welcoming of people’s learning accommodations and learning disabilities,” said Brad.

Yet, is the current system sustainable? In this situation, timing is everything.

The print version of this article distributed on Wednesday, February 19, 2025 included the sentence “In previous years, small group tests would be proctored in the upper floor of the Library.” Dr. Ramos has since indicated that this is inaccurate.

![(from left to right) Nathaniel Hendrickson (‘31), Benjamin Hill (‘31), and Cameron Sibley (‘31) are all smiles as they pet Brady, Ben’s spotted dog, who was blessed. “[Brady] was very excited and happy to be there,” he said.](https://thebishopstower.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-13-at-8.45.50-AM-1200x899.png)

![Leia (‘30) and Sara Park (‘32) ended their combative performance with a yell known as a kiyap. Leia explained with a proud smile, “I realized this when I was little, but not many people see taekwondo every day. For me, it’s a daily occurrence, so it feels very normal…when I do [a performance] in public, everyone’s like ‘Wow, that’s really cool’. So it always reminds me how this isn’t a normal thing in other people’s lives and I think it’s really cool that I can share that.”](https://thebishopstower.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-02-at-2.07.47-PM.png)