“Already last year, we knew that it was a new landscape of writing,” English Department Interim Chair and Teacher Ms. Catherine Michaud said. This landscape is defined by inauthenticity — searching for and relying on shortcuts made possible by the rise of generative AI. In seeking a way to combat this change, the English department prompted a possible solution: timed writings.

AI has developed rapidly in recent years with the creation of ChatGPT, which has the distinctive ability to converse with users. English II student Maya Krishnan (‘27) reflected, “AI works the same as Google, only with more efficient answers, making it feel like I’m talking to a person.” Before the rise of AI, Ms. Michaud explained that students used the internet’s pre-written content such as sparknotes or study.com to help gather information and synthesize their ideas. However, AI is not only helping students brainstorm ideas. It’s also giving students the words.

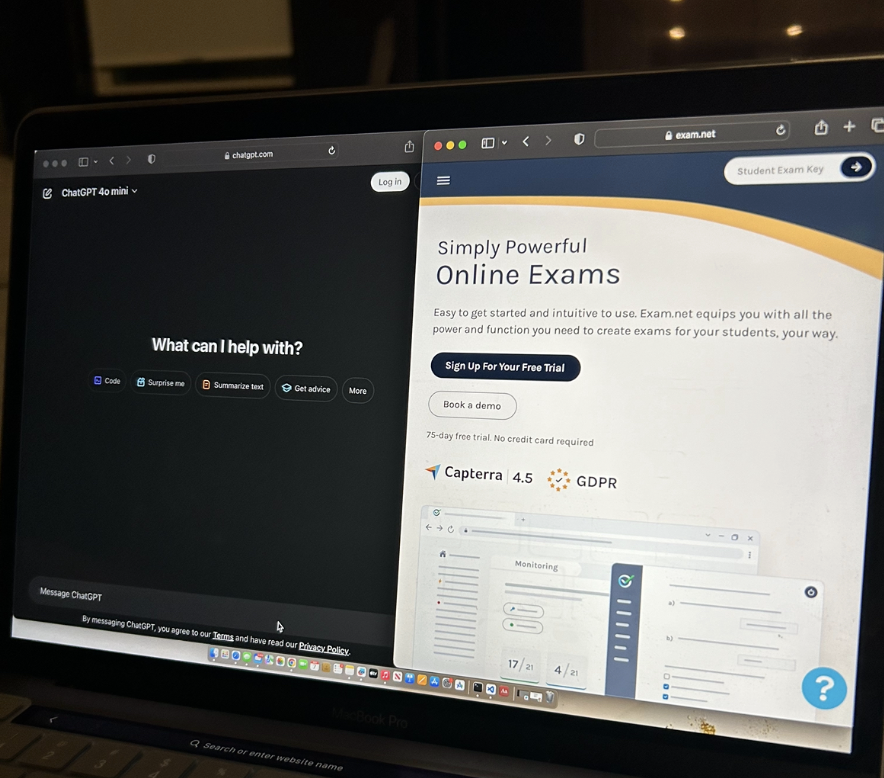

AI can write essays, and it can write essays in various tones, styles, and formats. It adjusts text almost instantly. ChatGPT is among the many platforms that can change a writer’s voice and tone, another being Grammarly’s recent AI update. The development of tools that can write in such a customizable way has significantly impacted English classes at Bishop’s — especially written assessments.

In math or science classes, students might use AI as a study aid, but during tests students rely entirely on their existing knowledge. In English, however, most of the assessments have been processed essays. Processed essays, English teacher Ms. Amy Allen explained, allow students to “start an idea, set it down, move away, come back to it, rethink it and rethink it.” Although more critical thinking occurs during processed essays, Ms. Allen explained, students are increasingly turning towards AI to do that work for them.

In some ways, more general concerns over how much of processed essays are really individual students’ work have surfaced because of AI. The question of how much students are independently working on their essays — and to what extent they’re receiving help from not only AI but their peers, families, and tutors — have risen to the surface.

English teacher Dr. Clara Boyle added, “[AI] has made me more vigilant. If a student turns in an essay that has really smooth sentences, I wonder whether Grammarly edited their sentences or whether they copied and pasted their essay into ChatGPT and asked it to clean up their sentences.” Harboring worries about AI use, teachers have shifted to timed writings. “Authenticity is the name of the game,” Ms. Michaud explained. “Anything that we do, we want it to be a product of a student’s own thinking and feeling. Otherwise, why? What’s the point?” She concluded, “In-class writing is the only way we can guarantee that it is that student’s authentic work.”

Most of the English department has increased the amount of timed writings this year, Ms. Allen said. Honors American Literature student Sophie Brunner (‘26) explained that she has written three timed essays so far this semester, while last year’s students in the same class had one timed essay the whole year. Ms. Allen explained, “I spoke with my department chair today, and she expressed surprise that teachers would assign any essays that allowed students to use AI assistance on their papers, particularly Grammarly.”

Some students have adapted to the focus on timed writings. Sophie explained, “I wasn’t exposed to timed writings last year, but I think they’re okay. I spent an absurd amount of time on the processed ones.” Honors American Literature student James O’Brien (‘26) agreed, and added, “I hate spending hours on an essay. Time writings help me not overthink my ideas so much, and teachers have a slightly lower standard.” Ms. Allen attested to that idea, saying “I’m more lenient. I’m a little more forgiving if essays are less creative than I’d hoped they would be because students don’t have time to revise.”

However, while some students prefer this limited amount of time, others struggle with it. English I student Kalina Parikh (‘28) said, “I really don’t like timed writings because I think they’re very stressful and I usually end up rushing to finish. It’s better if we have more time to think about it because then we’ll get more out of it and be able to learn the material better.”

Timed writings guarantee authenticity, but they also lose something central to writing: the process. As a result, Dr. Boyle still primarily assigns processed essays in her English classes. “It would be a loss for students not to go through the writing process,” she said. “AI is just a risk built into processed writing, and I’m willing to take that risk for now.”

Ms. Michaud agreed with Dr. Boyle’s characterization of writing as an iterative process. More specifically, that the nature of writing requires creativity, critical thinking, discovery, and revision. “You use writing as a tool to learn and discover,” she said.

One of the reasons why the English curriculum has shifted to timed writings, Ms. Michaud continued, is because using AI short circuits students’ creative thinking. AI turned into a barrier, blocking students from the world that they are supposed to discover through the process of writing. Dr. Boyle added, “[By using AI], you miss out on the way that you grow as a thinker.”

Writing, especially essays, Ms. Michaud explains, is inherently a difficult task — no good piece of writing comes without frustration. But it is through this process that students learn and discover. She added, “AI instills a sense of self doubt. We would rather have students lean into the difficulty and frustration than to be like, ‘It’s too difficult, I’m too tired, I don’t like this. Let’s see what the bot has to say about it.’”AI is slowly turning into a tool that students depend on. Ms. Michaud described, “Students use AI as a crutch, rather than as an inspiration.”

Dr. Boyle explained, “my worry is that students will never learn to do the thing and then will eventually come to believe that they can’t. And that just feels like a real loss.” Ms. Michaud added, “I worry about students with goodwill and integrity who value their own learning the most, because if they see their peers taking shortcuts they might actually compromise their own learning. One of the reasons that I love this school is because we have students who genuinely want to learn. And I am afraid for them.”

However, if students are able to find that balance, AI can benefit their learning and studying experience rather than obstruct it. Ms. Allen described that students could use AI to define terms they may not be familiar with in the context of their book or ask AI to explain allusions and references. Kailin Xuan (‘26) explained, “AI can clarify something for you and break it down into something simpler that makes it easier for you to understand the material.”

Honors American Literature student Eleanor Meyer (‘26) added, “There are definitely ways in which Al has enhanced my learning experience. I think the main issue is that Al is so accessible. It’s hard for students to know when their acceptable use turns into taking advantage of the tool at their fingertips to a point where it’s only harming them.”

Alongside harming students’ learning experiences, AI could have a cultural impact on writing and the humanities. Dr. Boyle concludes, “I worry that the culture will decide that because computers can write, people shouldn’t have to learn how to write anymore.”

While AI can shorten hours of research in seconds or write with perfect grammar, there are aspects of writing humans excel at that a robot can’t do. Eleanor concluded, “We have feelings, and we are able to express them with way more meaning than Al can since it’s only trained on other people’s experiences yet has none of its own. We aren’t artificial. That’s what we have to embrace.”