“China as a country is represented by the government, but Chinese people are not correctly represented. Their opinions are not reflected,” said Math Teacher and advisor of Bishop’s East Asian Student Association Dr. Jay Zhao.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, anti-Chinese sentiments escalated throughout various media platforms, such as Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram. Four years later, due to the negative portrayal of China in addition to the deep-rooted sinophobia problems of the U.S., many media users are expressing ignorant views of Chinese culture as the media has been negatively portraying it for years. Users are unable to separate Chinese people from their government, and this has had a profound impact on how Chinese culture is portrayed in videos, leading to cultural misunderstandings.

Sinophobia stems from the history of hostility shown towards the Chinese in the U.S., dating back to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This hostility was further stimulated in 2020, when former President Donald Trump referenced COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” and the media promoted his negative views. According to research done by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, anti-Asian hate crimes rose by 339% in 2021.

Additionally, the U.S. Senate’s potential “TikTok ban” in 2023 further exacerbated anti-Chinese sentiments, as senators targeted TikTok because the parent company, ByteDance, is located in China.

In March of 2024, the House of Representatives passed a bill that threatened to ban TikTok nationwide, unless ByteDance sold the app. Many of the worries that stem from the ban are related to China’s authoritarian government and intelligence gathering, and the American Office of the Director of National Intelligence said in a report released in February 2024, “the Chinese government has used TikTok to influence recent U.S. elections.” CNBC added, “Lawmakers from both parties have claimed that TikTok poses a national security risk because of the app’s alleged ties to the Chinese Communist Party.”

However, AP News explained, “The U.S. government has not provided any evidence that shows TikTok shared such information with Chinese authorities.” Furthermore, BBC News explained that, according to TikTok’s Chief Executive Officer Shou Zi Chew, the company is committed to keeping its data secure, and its platform “free from outside manipulation.”

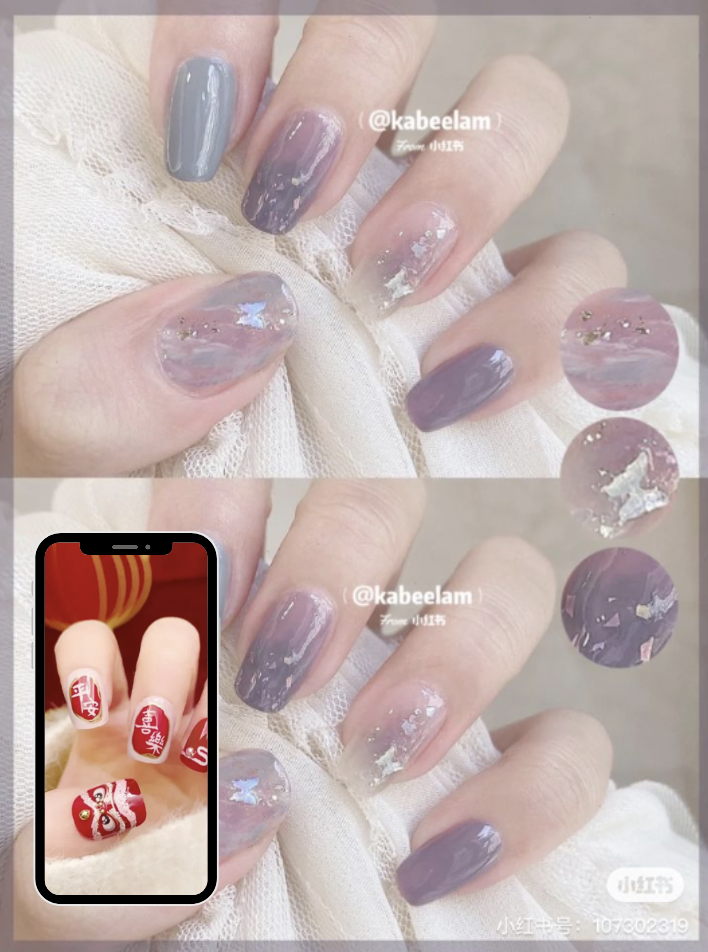

Whether or not these allegations are true, these political tensions have extended to a skewed portrayal of Chinese people, culture, and trends across the internet. Social media often hides the beauties of Chinese culture, and Chinese makeup, nails, clothing, and food, among others, are being rebranded as Korean or Japanese.

EASA leader Kailin Xuan (‘26) explained, “It’s easy for the media to just portray one side of a story, ignoring how diverse [Chinese] people really are.”

A lot of this misinformation comes out of social media’s algorithms. A study from Boston University in 2024 found that between 30% and 50% of videos that TikTok users see are recommended based on their prior engagement.

Whether it’s because of the history of hostility shown towards the Chinese, or the simultaneous rise of Korean and Japanese culture in Western media, views towards Chinese culture are incomplete or inaccurate as a result of the algorithms of the media.

Recently, tanghulu, a Chinese snack that has existed in China since the Song Dynasty in 1000 A.D., was headlined “Korea’s candied fruit” by the San Francisco Chronicle. The article later specified that the snack is originally from Northern China, but the focus on its current popularity in Korea reflects the deprioritization of its Chinese origin. Tanghulu’s hidden roots is just another example of the media’s effect on the broader issue of sinophobia.

Moreover, a video on Twitter posted in 2023 depicted an airport staff member caring for luggages at an airport, with the hashtag “Japan.” The comments were filled with, “I swear the Japanese people are the most respectful people,” and “There is so much to learn from them.” However, the video was taken at an airport in Zhengzhou, China, and reposted from Douyin, a Chinese social media platform. The Twitter account had 1.8 million followers.

The origin of this video was obscured because it was taken out of context, and the user posted it and applied his own stereotypical thinking. The media is a fast way to spread information, but this makes it easy for it to be misleading. It’s not that media users were refusing to accept that the person in the video was Chinese; rather, misinformation spread from one platform to another, and widespread negative Chinese depiction on the internet led to an automatic assumption that she wasn’t.

These misunderstandings have even resulted in Chinese companies rebranding themselves and hiding their origin as a business strategy. The fashion brand Shein, originally headquartered in Nanjing, China, relocated its company to Singapore in 2021, deregistering from its original company in Nanjing. Lester Ross, chair of the American Chamber of Commerce in China’s Policy Committee, explained that many companies are relocating to avoid the risk of criticism, believing that they will become a global company if they shed their Chinese image.

Additionally, Miniso, a Chinese company, admitted to and apologized for rebranding themselves as Japanese as a “global branding strategy.” Additionally, the only verified TikTok account of the Chinese makeup brand Flower Knows is in Japanese.

As companies use social media platforms such as TikTok to promote their items, aiming to make themselves more palatable to a Western audience by hiding their Chinese roots simply showcases the issue of sinophobia, and how the media further encourages it.

Dr. Zhao concluded, “Ordinary people are always influenced by the media… and they often have very one-sided stories. It’s all about the big picture.”