“In racing there are always things you can learn, every single day. There is always space for improvement, and I think that applies to everything in life,” said Lewis Hamilton, Formula One (F1) driver for the Mercedes AMG Petronas F1 Team. And he is exactly right — especially when it comes to Formula One. The pinnacle of motorsport is all about achieving the unachievable.

F1 is a daredevil sport that offers money, fame, and luxury cars. But lesser known, F1 also offers scientific discovery.

Research is a Team Sport

An F1 team is like a research team, all working to better their product: the race car. In F1, team success relies not only on driver skill but also on team collaboration. Each team maintains 300 to 1,200 employees, including 15 to 20 engineers in the pit during races and up to 80 people connected to radio channels, all working to collect information from the race car. This network of information is funneled to the driver through the race engineer, Lewis Hamilton’s long-time partner, Peter Bonnington (Bono). In an interview for the New York Times in 2022, Hamilton praised Bono for helping him win six of his seven F1 championships. “If the driver trusts the team and vice versa…then you’re a team and fighting as one,” Hamilton explained.

The F1 Process = The Scientific Method

Any discovery in science starts with an observation.

F1 teams follow strict rules established by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), which regulate what teams can and can not do to the car during the season. However, under “parc fermé” (which translates to “closed park” in English) conditions, teams have a list of acceptable changes. For example, for the Miami Grand Prix held in May of 2023, Ferrari made subtle floor and diffuser changes after noticing the car struggling with braking, entry, and exit phases. Changes like these keep the car running between races without overly or unfairly enhancing car performance.

From observations, scientists formulate hypotheses and test them through experiments.

At the end of the season, teams analyze their data and identify areas of improvement. Then, back at headquarters, their team designs and engineers a new car for the upcoming season, overseeing everything from parts procurement to production.

MagCanica, founded in 2000 and based in San Diego, California, is a company that produces parts for F1 cars. According to Nader Bitar (Sami ‘28, Nora ‘25, and Nadia Bitar ‘22), Vice President of Business Affairs and Chief Financial Officer of MagCanica, 80% of their clients are in motorsport, and all ten F1 teams buy torque sensors from their company.

Mr. Bitar explained that currently teams often request custom built sensors, but with more FIA rules and regulations to come, car parts may become more standardized. “The next rule change takes place in 2026, and there are engineers already developing new cars for that year,” Mr. Bitar added. Year-round, F1 teams work continuously on old and new cars, comprising approximately 14,500 parts each. Meanwhile, drivers use race simulators to practice and memorize tracks, intensifying training during the three-month off-season.

Finally, scientists share results.

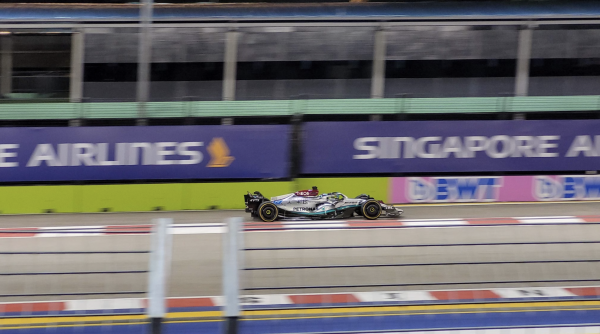

In F1, the sharing of their experiments are the races themselves.

This is also where the dozens of advertisements, interviews, movies, and shows come in to help push the sport to the world. Even though teams have a completed set car for the season, just as there is always a question to be answered in science, there is always a problem or part to be improved in a F1 car. As Geoffrey Willis, the Director of Digital Engineering Transformation for Mercedes said, “The thing that keeps me driving in Formula One over all these years is [that] you have always got a new problem, and you have got a lot of people to help tackle that problem.”

The F1 Track = An Experimental Lab

F1 is a team-oriented sport and runs like a group of researchers does in a lab, so it is only natural that they propel advancements in automotive technology. The sensors built into road-cars come from the long line of 400 sensors attached to race cars during Friday test-drives.

F1’s constant enhancement of driver safety can be seen through the fire-proof suits and safety cars. For instance, the official medical car for the 2023 F1 season, the Aston Martin DBX 707, is equipped with an extensive array of emergency gear, as well as FIA-approved racing seats and harnesses.

The races themselves are like meticulously conducted experiments, with each race track serving as a unique testing ground for the cars and their components. The outcomes, specifically the winning driver and car, serve as a direct measure of the effectiveness of these advancements, contributing to the ongoing evolution of the sport.

Formula 1 = A Race to Discovery, Not Just Podiums

Without effective marketing, F1 would be merely a costly “engineering competition,” Mr. Bitar said, and “not just a driving competition.” Mr. Bitar emphasized that “other racing series limit what [teams] can do,” and F1 instead encourages teams to push for the extreme to meet lofty specifications. Just think of the car engines — F1 cars, with 1,000 horsepower, outspeed Formula 2 (F2) counterparts (620hp) by 10-15 mph on average, hitting top speeds over 230 mph, while F2 cars peak below 200 mph. This fosters advancements in various fields, including car engines, aerodynamics, consumer electronics, medical technology, and urban design.

One example is the shift from 30% to 50% thermal efficiency in racing cars in a mere five years from 2013 to 2018. The upcoming second-generation carbon-neutral hybrid power unit in 2026 will further cement F1’s role as a testing ground for hybrid technology in road cars. In a modern world that strives for efficiency, F1 turns it into power and speed.

This intricate sport locks in passionate fans like Novalyne Petreikis (‘23) who watches “races on replay when [running] on the treadmill,” and Lila Hampers (‘24) who “wake[s] up at four AM” in order to watch races live.

Under all the glamor that surrounds F1, at its core it drives technological advancement. As F1 curves towards clean energy (the formation of Formula E), so will roadcars. Races are experiments for teams, making F1 one global science fair intertwined with hefty sponsors, politics, and millions of livelihoods.

![“I [look forward to] the adrenaline of just competing with your friends and playing a sport that I’ve loved for so many years,” Sydney Mafong (‘26) said. “It’s just unmatched.” The Softball team celebrates a victorious moment in the game against San Diego High School on March 15th during the Torrey Invitational, which Coach Joe “Joey” Moreno called the “first real test of the season” in a Locker Room email and won 10-3.](https://thebishopstower.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-03-17-at-21.49.22-1200x1016.png)