A Very Fine Line

It would be nice to think we could change the world with the click of a button

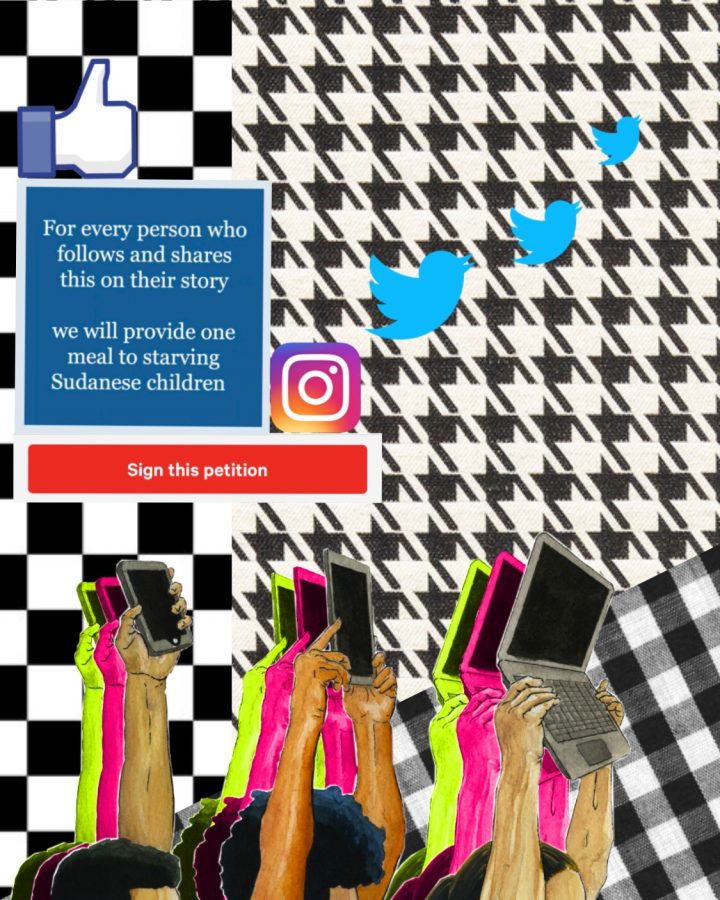

Slacktivism refers to actions taken to support a cause – actions requiring minimal effort on the participant’s part. Art by Sariah Hossain (’22).

You smell something burning before you see it. There’s suddenly a bite in the air that wasn’t there before, and there’s a few moments of well-intentioned ignorance, then a few moments of confusion, a moment of understanding, and then you rush to the kitchen to try to fix whatever went wrong.

Right now, we’re in that moment between innocence and action when comparing the wish to do good in the world with the way we go about doing it. Send a tweet and join an online petition or participate in a protest outside City Hall? There’s a difference between the two that’s a step deeper than face value. There’s a term, “slacktivism,” sometimes pejoratively called “clicktivism” or “armchair activism.” The Mirriam Webster dictionary defines it as “the practice of supporting a political or social cause by means such as social media or online petitions, characterized as involving very little effort or commitment.” We’ve all seen this before, whether it be through social media accounts or through, well, being a member of society in the 21st century. And while it’s a step in the right direction, it isn’t quite enough.

The term first came into use in the late 1990s. According to the New Yorker, it was meant to shorten the phrase ‘slacker activism,’ which at the time referred to activities intended to affect society on a more personal scale. It meant planting a tree in a community garden rather than taking part in a protest, and the term originally had a positive connotation.

In the following decades, it grew to encapsulate more than small-scale good deeds. With the growing influence of the internet and social media, its definition evolved into its modern form. Consider movements as large as #BlackLivesMatter, that campaign against systemic racism towards black people, and the Arab Spring, a series of anti-government protests that gained traction almost entirely online. Modern-day activism is intimately tied to the internet. It seems to be making a difference as well, shown through studies done by New York University and the University of Pennsylvania’s data science and communication schools. They analyzed Twitter activity during the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement, protests located on Manhattan’s Wall Street against economic inequality. The network effect created, they found, led to exponential increases in engagement, which meant the message of the movement was heard by far more people than if social media hadn’t been involved. “Words are as loud as actions,” wrote a Quartz article detailing this phenomenon. But that’s not how the saying goes— is it?

Slacktivism has most recently manifested in Change.org and steel-blue profile pictures. In May and June, the crisis for democracy in South Sudan reached global headlines. Instagram users began to change their profile pictures to a solid blue to show solidarity with Sudanese protestors. Soon one couldn’t scroll through their feed without seeing it. People would share posts with hashtags on their Stories, a feature of the app that allows users to put up images to be viewed for 24 hours and then deleted. A few accounts rose to fame, all variations of a ‘Sudan meal project,’ claiming that whenever someone shared or liked their post, a meal would be provided to Sudanese children. When The Atlantic and CNN examined these accounts’ promises, they found that no action was taken by their owners. Still, @sudanmealproject had amassed over one million likes.

I had liked the post, as well as a large number of my friends. Everyone wanted to do their part. The stories spanning the news told of a humanitarian crisis– of course, people wanted to help. But was this the way to do it? It seemed, at least in part, to be a front. Were we also trying to show the world how socially and politically aware we were? Had it become trendy to be an activist?

For the most part, that’s not at all the case. The vast majority of people want to help. Spreading awareness of a problem or injustice is moral and commendable, but it’s also just a start. If the measure of success is in the outcome, is a difference being made in Sudan when I tweet out a hashtag? Maybe, someday, if ten or twenty more reactions happen after I send that tweet – the snowball effect, one might say. But as for myself and for my actions, they don’t guarantee anything– regardless of the good intention or compassion I have while doing it. That’s the dual-edged sword that digital activism presents. Right now, I am just the first step. A starting point. But really, all of us have the potential to be more.

Sariah Hossain is a senior and The Tower's Co-Editor-in-Chief. This is her fourth year on the publication and, as her friends can all attest, writing...