Literally, Literally

How the use of the word ‘literally’ has changed over time

The use of literally has changed over time. As the younger generation seems to have created their own definition for the word, misuse of literally has become more common.

“I’m literally going to die,” says your friend before a big test. Even though the way they used the word ‘literally’ meant that they were going to die, the next morning, you see them alive and well and not the least bit dead.

Jean Berko Gleason, a psycholinguist and member of the Psychological and Brain Sciences Department at Boston University, studies how we acquire and use language. “My impression is that many people don’t have any idea of what ‘literally’ means – or used to mean,” she said, “The new ‘literally’ is being used interchangeably with words such as ‘quite,’ ‘rather,’ and ‘actually.’”

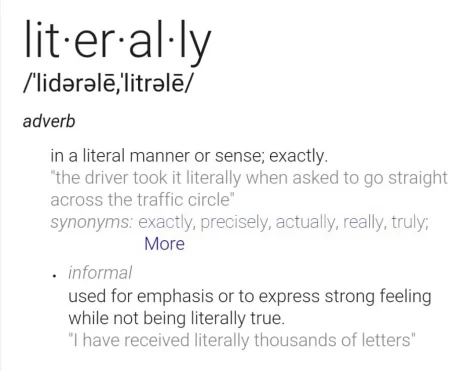

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the word ‘literally’ is literally an adverb that means “in a literal, exact, or actual sense; not figuratively, allegorically, etc.” The alternative definition the OED says literally is also used “to add emphasis.” However, many people also use it colloquially in a figurative sense and as a filler word.

Among the younger generation, literally seems to have taken on a new meaning. According to Riley Lincoln (‘25) it is used for its figurative definition and for emphasis. When asked how she used the word, Riley said, “I feel like it means to be exact or precise, but I use it for the opposite, almost sardonically.”

Similarly, William Guo (‘24) felt that there was an overlap in how people used the word ‘literally.’ “When something is serious, and that is also true, there is not only emphasis, but there is some truth to it,” he said. For instance, William used the example when people say they are going to literally cry from the AP test. Although, they are not literally crying from the AP and are exaggerating their feelings, they are serious about the fact that they are experiencing a stress that makes them want to cry.

The word ‘literally’ has shifted throughout time, hence the complex etymology of the word. “Language is continuously evolving and although that evolution has slowed down a bit because more people have become literate, language is constantly changing,” said Mr. Matthew Valji, who teaches History and Social Sciences and coaches Speech and Debate. He went on to explain that the way people use words like ‘literally’ changes between different generations and groups of people, making “it difficult for intergenerational or intergroup communication.”

Mr. Valji also hears the word ‘literally’ pop up in discussion during class. “I think there are two phenomena going on with the word literally. One being a possible change in definition from its [original] use and meaning, and the other phenomenon is that it is used as a filler word, where deleting the word from a sentence in no way changes the meaning of the sentence,” he theorized.

William confirmed Mr. Valji’s statement when he considered his science teacher. “He sometimes likes to use ‘literally’ and puts a lot of emphasis on [the word]. He usually uses it to mean ‘in a strict sense.’” William then went on to say that, in contrast, he and his friends used the word for exaggeration.

English Teacher Mr. Adam Davis said he hears ‘literally’ used about 50-90 times during discussion. “I love the word but dislike the current usage because it devalues its meaning through repetition,” said Mr. Davis. “What grates me is when we all use the same filler words. There are so many wonderful filler words out there, so why use the same one everyone else is using?”

The amount of filler words one uses often attributes to the impression one gives off. Ellie Hodges, a senior who participates in Speech and Debate, felt that speech and debate dramatically decreased the frequency with which she uses filler words like ‘literally’ and ‘like.’ “I used to say the word ‘like’ all the time, and then I realized how much I was saying it largely due to speech and debate,” she said. Ellie went on to say that “the way you sound really matters and filler words make you sound like you’re not confident.”

Misusing the word literally—as a filler word and colloquially— in professional situations reveals a misunderstanding of the word. “You will sound more prepared and better educated if you use fewer filler words and will ultimately be more persuasive,” Mr. Valji cautioned. He recommends talking slower and being okay with brief pauses.

Summer is a senior and Editor-in-Chief of The Tower. This is her fourth year on the staff and third on the editorial team, previously serving as a story...