The Great Sizing Dilemma

A dive into the timeless problem that is vanity sizing

“[Vanity sizing] is a much farther-reaching problem,” said costume designer Mrs. Jean Moroney.

Marilyn Monroe, the American actress, model, and singer who was one of the biggest style icons of the 1950s, was a size 14. For some, this may come as a surprise. However, it is completely accurate by the sizing standards of that era. Today, Monroe would be around a size 6. Why?

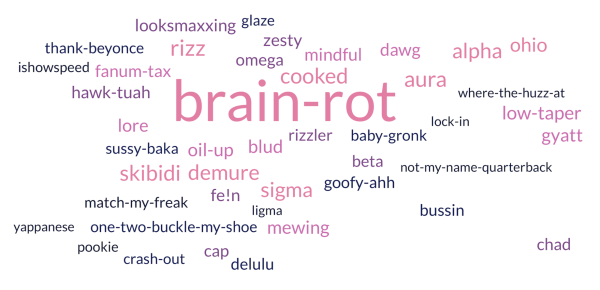

Vanity sizing, also known as size inflation, is the practice of labeling clothing items a smaller size than the measurements actually reflect in order to encourage sales. Over the past 50 years, it has become an unfortunately apparent issue. If you’re a size medium and are occasionally perplexed when a shirt labeled a size small fits perfectly, you have likely experienced vanity sizing for yourself. On many different levels, vanity sizing is a problem that needs to come to an end.

Simply put, clothes are meant to fit you—you are not meant to fit into clothes. “We purchase what we can, hoping for the best, becoming angry at our bodies for not corresponding to the coverings instead of the other way around,” wrote journalist Tracy E. Robey for Vox.

First of all, on a surface level, vanity sizing is a frustrating inconvenience for any woman shopping for clothes. For example, data analysis from True Fit taken from $40 billion worth of transactions across retailers shows that the waistband measurement of women’s high-rise jeans in a size 6 can vary by more than five inches. If a particular size is a different measurement everywhere, there is no longer any point to sizing at all. “[This destandardization] makes shopping online harder, since you never know how something’s going to fit,” added Renee Wang (‘24).

“It’s difficult for us,” said Costume Designer and Performing Arts faculty member Mrs. Jean Moroney, referring to the costume design department as a whole. “If you look at the patterns that we use, I can guarantee it’s not the same size you wear if you go to the store.” Mrs. Moroney reflected that in her career, she has always had to deal with sensitivity surrounding sizes. “We’re very careful not to let people know their pattern size,” she said, “because they care.”

Additionally, size inflation is impractical, as it will only accelerate as the years go on. Sizing data from the National Institute of Standards and Technology, presented in a study by the American Society of Testing and Materials, shows that in 1958, a women’s size 8 was a measurement of 24 inches around the waist. Today, however, a size 8 is 30 inches. To compensate for this inflation of sizes, a size 4 had to be introduced around 2001, followed by 0 and 00 around 2011. If the trend continues, eventually, companies will have to either add more zeros or go into the negatives—which would be absurd.

Most importantly, brands such as H&M, Forever 21, and Free People manipulating their customers in this deceitful manner is simply unethical. Size inflation is not a coincidence—clothing stores are fully aware of the effects sizing has on our minds. A new study from the Journal of Consumer Psychology (JCP) proved that larger sizes result in “negative evaluations of clothing,” driven by the consumers’ self-esteem. Not only are customers more likely to buy an item with a smaller label, they may also engage in compensatory consumption, purchasing more items to help repair their damaged self-esteem from requiring a larger size. This establishes the manipulative relationship between consumers and clothing sizes, in which the act of shopping can serve to subconsciously affect consumers’ mental health.

Mrs. Moroney feels that it is much less of a problem in men’s clothing. “Men aren’t as afraid to go up in size as women are,” she said, explaining that she believes this discrepancy is based in psychology. Statistically, it remains unclear how clothing sizes impact men. However, as the JCP study (which focused on women’s clothing) postulated, “It is possible that rather than mirroring their female counterparts, male consumers are instead ambivalent to sizing labels, or perhaps even exhibit the opposite effect and actually hope to be “bigger” in some sizing contexts.”

At the end of the day, vanity sizing promotes toxic views on body image that women already have to deal with. There is no immediate end to this problem in sight, as Mrs. Moroney put it – “not unless women get a backbone about this.”

Overall, vanity sizing is certainly a problem that is rooted deeper than just the numbers and measurements. “It makes women nervous and can encourage eating disorders,” said Mrs. Moroney. “I think it’s a much farther-reaching problem.”

Isadora is a senior and an Editor-in-Chief. A four-year member of The Tower, she loves to write about a variety of topics, from school coverage to national...

Shirley Xu is a junior and this is her first year on The Tower. She has been a writer since the ripe age of three, and is excited to share her journalism...

![“[Vanity sizing] is a much farther-reaching problem," said costume designer Mrs. Jean Moroney.](https://thebishopstower.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Untitled_Artwork-826x900.png)