Something Borrowed, Something Blue

A look into the conception and message of the fall PDG show

In the fall PDG show this year, Ms. Cory and the dancers portrayed a world of underwater life to demonstrate the impact that plastics and pollution have on the environment.

“From where you sit, the ocean is a block away. So close it’s personal… We ‘claim’ it, foolish humans that we are… We are temporary beings, simply passing through. May I humbly offer, as we contemplate our relationship to the planet, more respect is in order,” Director of Dance Ms. Donna Cory said in the program for Blue.

If you attended the fall Performing Dance Group (PDG) show, you likely noticed the blue lighting and the plastic bottles littered across the back of the stage. This year, PDG performed Blue, a commentary on the amount of plastic that humans deposit in the oceans and its detrimental effects on wildlife and the earth. So how does this show manage to convey such a complex message through dance?

While many forms of art, both across the Bishop’s campus and across the globe, have hidden meanings, in Blue, the message comes to the forefront clearly. “Every performance we have is a chance to speak out about a certain issue or make a commentary on a story,” Elise Watson (‘22) explained.

The title of the concert, Blue, may at first seem to simply refer to the blue of the plastic and the ocean. However, it also references the blue we associate with melancholy. This feeling comes through both in the title and blue lighting. “I think of being blue as just sort of stuck in neutral,” Ms. Cory said. “We spent a lot of time talking about how we all see the problem [of pollution]. We all agree… Now what do we do about it?”

Members of PDG began collecting plastic months before the performances, both to use as costumes, props, and parts of the setting. “The [sheer] amount [of plastic] that we use everyday made it easy to collect so much in such a short amount of time,” Elise said. Dancers wore the plastic as a part of their costumes to emphasize how much the material is involved in our daily lives. “I think the amount of plastic we collected was a pretty harsh reality check of just how much plastic we consume,” Michelle Lai (‘22) pointed out.

The cover art of the program, by Ellie Hodges (‘22), depicts the ocean, but with masks and plastic soda bottles floating in it. “I designed it based on a couple of full photo references that Ms. Cory sent me,” Ellie noted. “It’s not obvious in the photos on the program, but I actually painted on this canvas that had bubble stickers already on it to mimic the ocean.”

In the program’s From the Director letter, Ms. Cory provided a list of facts and statistics about sustainability, plastic, and wildlife, as an introduction to the show. “We aren’t helpless,” she concluded. “We can make a huge difference.”

Blue displays the passage of time, ranging from the creation of the universe to humans today that throw plastic into the ocean. In one of the first pieces, “Origin Story,” Seniors Robert Devoe and Ashlyn Hunter took the places of hydrogen and oxygen respectively as they showed the formation of water as the creation of the universe.

In that same number, Michelle Lai took the role of “La Luna,” or “the moon.” She performed a clapping motion that originated from Ms. Cory’s research about the role of the moon in controlling the tides and rhythm of the earth. The movement reappears at the end of “Plastic Soup,” but the rhythm is disjointed in its second appearance. “As [humans] destroy the earth, we are also destroying that rhythm that keeps the earth healthy,” Michelle explained. “[In “Plastic Soup”], I am trying to find that original rhythm but can’t.”

In the following number, “Plastic!,” four dancers who are not members of PDG—Riley Brunson (‘25), Sophia Gleeson (‘24), Annika Haagensen (‘22), and Mira Singh (‘25)—took the stage in black suits and brightly colored skirts. Sophia, who has been enrolled in Studio Dance Group (SDG) instead of PDG this year due to scheduling conflicts, explained that “‘Plastic!’ was modeled after an advertisement for plastic in the 1960s and 70s.” The dance depicts the rise of the material into popularity. “It was glamorized at the time for being cheap and really easy to manufacture,” Sophia said.

“Plastic!” is one of a few pieces in Blue in which the dancers took the place of humans, rather than ocean creatures or inanimate objects. “You go for 20 minutes before you encounter someone who is portraying a person,” Ms. Cory said. “We were trying to create another world.”

In perhaps one of the most striking numbers—“Beach Party!!!”—the full company took the stage in what seems on the surface to be a sunshine-filled beachy celebration with music to match, complete with bikinis, rainbow towels, and picnic lunches. However, at the end of the dance, the characters left behind their piles of trash and food. “It’s not a happy dance,” explained Sharisa You (‘22). “It’s a mockery.”

Towards the end of “Beach Party!!!”, dancers left the stage and began talking to the audience members, handing them plastic containers. “Would you like some plastic?” they’d say. Or, “Take a piece of plastic.” This technique of involving the audience is called breaking the fourth wall and refers to the imaginary wall performers envision to separate themselves from the audience (and then break). It is especially effective in a show like Blue with such a strong real-world message. “Breaking the fourth wall… leaves [the viewers] with this piece of plastic to hold and look at.” Lila Hampers (‘24) explained. “This is a moment for the audience to reflect upon themselves.”

At the end of the show, they returned with plastic bins, asking the audience members to give back the trash. It was a call to action, conveying the idea that humans (represented by the audience) could save the ocean if they worked together. Ms. Cory explained that audience involvement is atypical in her fall dance concerts. However, the story of Blue is not localized within this concert. “The protagonist of this dance concert is water,” she noted. “And the antagonist is us.”

Blue is only forty-five minutes: both so that it sticks with the audience and so that the dancers had time to learn all of it while regaining their footing after the pandemic. Ms. Cory noted that she would have liked a little more time in this particular aspect of the performance—between handing out the plastic and picking it up. “The audience needs to sit with that plastic a little while longer… I think there needs to be more struggle.”

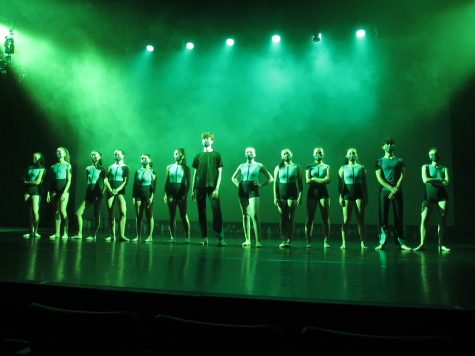

The performers involve another form of audience involvement in “Turtles,” which comes before “Beach Party!!!.” All fourteen dancers stand on stage and stare at the audience. “I very much choreograph for teenagers,” Ms. Cory explained about this section of the show. “That moment of staring at the audience is like, ‘We’re holding you accountable. Is anybody going to do anything here?’” Lila agreed, saying, “We make a statement… coming from a younger generation looking onto an older generation.”

Ms. Cory and the members of PDG wanted the audience to continue thinking about the show long after they left the theater. “We wanted people to walk out of that performance and think: how can I live more sustainably, what can I do to help the environment,” Lila said.

One way they did this was by passing out bottle caps to people as they left. “People were asking, ‘What am I supposed to do with it?’” Ms. Cory reflected. “And we were like, ‘That’s the point. You have it—Where are you going to put it?’”

These many techniques taken together, from those onstage to those outside of the theater, emphasize that the intention of the show was not simply to tell a story, but to inspire the viewer to make a difference. “It’s not evil people who contribute [to the trash buildups], but just regular people making little choices,” Eliana Birnbaum-Nahl (‘23) explained. “I think it felt personal, because everyone uses plastic and everyone has a trash can… In San Diego it ends up in the ocean.”

“I feel that movement is a universal language.” Ms. Cory said. “There are a lot of different verbal languages on this planet, but hugging somebody is the same in any language. I think that [through dance], you can send a universal statement… without any words.”

Clare Malhotra was born in Boston, Massachusetts and moved to La Jolla at age nine. She is currently a senior, and this is her third year on The Tower....