A Different Kind of Cool

The competitive stress culture that comes as a consequence of high-pressure schools

The nature of stress at Bishop’s is revealed in the conversations we have about it.

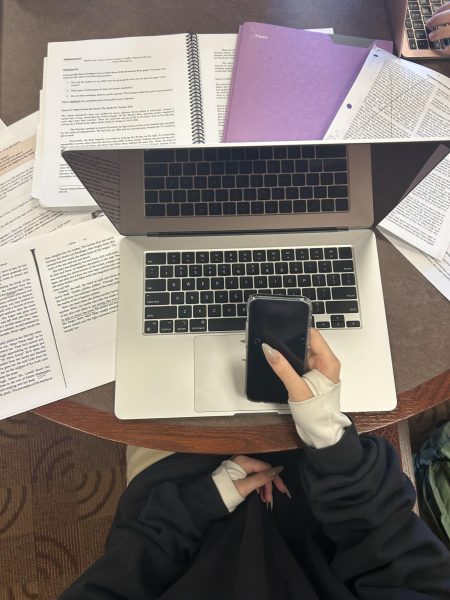

It’s a Bishop’s School tale as old as time. You’re standing in the skinny upper Scripps hallway, maybe dawdling outside the Cummins math corridor or making the cross-quad trek to the Science building with a few of your classmates. More often than not, the conversation goes something like this:

“I’m so tired.”

“Oh my god, same.”

“I only got four hours of sleep last night.”

They pause, waiting for the other person to ask, with a mixture of awe and worry, “Why?”

“Well, I had so much work last night, and you know APs can give double the amount of homework as regular classes. It’s so stressful. I almost had a breakdown”—a well-placed, self-deprecating chuckle here, so they’re not taken too seriously—“because I had practice after school, then volunteering, then I only got home and started my homework after nine. And I had to finish this paper, submit that assignment, take notes for this upcoming test… I had a coffee at midnight to keep my brain awake enough for Bio and then I couldn’t sleep until three.”

They shrug, and you can see the bags under their eyes and the worry lines that will surely crease their forehead sooner than they should, but still, their words come across as a brag. You return with:

“Haha, I started my homework at nine too, but only because I procrastinated until then. But I guess we ended up in the same boat.” Maybe, you think, you should think about early-onset stress wrinkles too.

…

There’s a particular kind of competitiveness that breeds among Bishop’s students, and it manifests in the ways we hold conversations about our workloads, stress, and mental states. Within the student body, being stressed is synonymized with working hard or being an admirable student. It’s treated almost as a symbol of valor, dedication, fortitude, or tangible justification for the pressure Bishop’s students juggle daily. There’s an undertone to the way we discuss this that perhaps is more of a net negative than a positive.

It’s a given, almost a cliche, that most high school students are perennially stressed, Bishop’s students more so than others due simply to the academic rigor the School prides itself on. “A different kind of cool,” the Bishop’s website reads. It’s a little funny, really, that said tagline is applicable to its students in more ways than intended. It encapsulates almost perfectly the culture surrounding workloads and stress at Bishop’s: it’s admirable to be stressed. It’s like a brag. It’s almost cool.

There’s an interesting inversion of social phenomena here with what college students have dubbed ‘duck syndrome,’ or the tendency of students to make out like their academic lives are totally stress-free (calm as the upper body of a duck floating above water) while in reality they’re all working extremely hard where no one else can see (paddling furiously like a duck’s legs underwater). At first glance, that seems to make more sense–though it is no less concerning–than the culture we’ve established at Bishop’s, one that’s almost a reverse of the aforementioned duck syndrome.

As such, it’s fairly easy to see that this I’m-more-stressed-than-you culture shouldn’t be the case, that this feels like a counterintuitive mode of communicating. “I feel like stress culture at Bishop’s doesn’t encourage us to be better students,” agreed Marianna Pecora (‘22). “It just encourages us to get less sleep.”

Stress culture as it exists at Bishop’s now is neither productive nor healthy. The question, then, becomes one of why it’s so pervasive on this campus of ours, more so than other comparable schools.

To be stressed is not an enjoyable feeling–we all understand this. A likelier explanation is that these one-ups of ‘I’m more stressed than you’ are ways to cope. Romanticizing something difficult, fancying it desirable or commendable in your head, is one of the most common methods I’ve found to drag myself through a difficult time (read: high school). Broadcasting how stressed we are under the guise of complaining is also a way to validate how hard we’re working, to prove to others that our struggles are real.

This ostensibly backwards way of conducting conversations about our academic lives may, then, in reality, be quite understandable reactions for overwhelmed teenage minds. We warp our all-nighters before Science tests or double-shot espressos before English discussions into gnarled medals of sorts–medals that look beautiful to us inside the Bishop’s bubble, but to an outsider, or to a parent, or to a teacher, they’re really only cries for help.

The tricky aspect is that this stress can be both warranted and unavoidable–there’s no reality where it isn’t a part of our high school lives. “A recent study surveyed and interviewed students at a handful of [academically rigorous] high schools and found that about half of them are chronically stressed,” New York University (NYU) senior research scientist Marya Gwadz said to the Atlantic. “The results aren’t surprising—between the homework required for Advanced Placement classes, sports practices, extracurricular activities like music and student government, and SAT prep, the fortunate kids who have access to these opportunities don’t have much downtime these days. These experiences can cause kids to burn out by the time they get to college, or to feel the psychological and physical effects of stress for much of their adult lives.”

And surely this isn’t a problem unique to The Bishop’s School—rather, it’s symptomatic of unhealthy student cultures at most any intense academic institution. Harvard-Westlake School, an elite college preparatory school in Los Angeles, wrote in their student newspaper The Chronicle of a similar issue: “Stress, anxiety and sleep deprivation have become terms that students use as social currency to prove they are working hard when in reality, they should not be valorized.”

Stanford University’s student newspaper the Stanford Daily agreed, writing that the same culture prevailed among their student body, and a stunt such as pushing oneself academically to “pulling three consecutive all-nighters isn’t a badge of honor… it’s okay to try to sleep nine hours a night.”

Bishop’s students might need to learn to take this to heart—I know I do. It’s difficult to practice self-care when the surrounding culture is one of such pressure and half-unsaid competitiveness; still, I urge you to try, and perhaps this begins simply in the walkway outside Cummins or on the cross-quad trek to the Science building when instead of showing off our stress medals, we talk about the Johnson & Johnson vaccine instead.

Sariah Hossain is a senior and The Tower's Co-Editor-in-Chief. This is her fourth year on the publication and, as her friends can all attest, writing...