#Canceled

Many other celebrities such as James Charles have gone through the dame process of being canceled over the past years; few have felt long-tern repercussions.

On May 10, the internet decided to present us with another, and perhaps its most well-known, scandal, involving infamous 20-year-old influencer James Charles, and his former mentor, Tati Westbrook. Westbrook posted a tell-all exposé surrounding the young YouTuber’s promotion of her rival’s vitamin brand in lieu of her own. Within minutes, Westbrook’s video accrued thousands of views and subsequently caused Charles’s subscriber count to plummet, losing three million subscribers in a matter of days. He had been canceled.

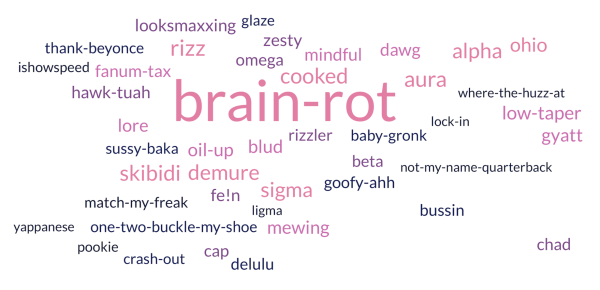

As a result of this internet-shattering scandal, many people took issue with Charles and voiced their frustrations by unfollowing him—the internet community’s way of communicating a message. This say-so the public has is perhaps why canceling is such a popular trend – it gives the general public license to hold people accountable for their wrongdoings. However, does normalizing the cancellation of celebrities neutralize its effectiveness?

The idea of cancel culture seems to be unproblematic or even beneficial for pop culture. In many cases, people have the best of intentions in trying to condemn something a celebrity has done, such as removing potentially harmful characters from public spheres of influence. Despite these intentions, impermanence seems to be a common thread amongst many celebrities that have been canceled. This is exemplified in the case of Charles, where he not only regained the 2.5 million subscribers he lost, but the whole scandal surrounding him was replaced by other controversies and, by and large, forgiven.

Jackie Cosio (‘22) stated, “The idea of cancel culture is pointless, but it’s great for people to gain relevance and increase their views.” Although the James Charles scandal made national headlines, prompting outlets such as CNN, Forbes, and the New York Times to write extensive articles detailing the star’s fall, it was replaced by another one soon after. Directly on the heels of the Charles’s scandal, another one involving YouTubers dubbed the “Dote girls” quickly captured public attention. These girls also faced punishments almost identical to Charles’, a similarity too commonly found on the internet to be a coincidence. The catch-and release process where stars like Charles are internet pariahs for a few days, then regain their views and subscribers only highlights societies broken internet culture. This is where the true problem surrounding cancel culture lies: the more influencers we cancel, the more the weight of the word canceled is corrupted.

It takes more than just will to cancel a celebrity; it also requires a complete social uprising. Lisa Nakamura, the Director of the Digital Studies Institute at University of Michigan, said to the New York Times on this topic, “It’s a cultural boycott. When you deprive someone of your attention, you’re depriving them of a livelihood.” Though this idea seems harsh, in reality, it never ends up having its intended effect. This is mostly because there is almost never complete agreement amongst the public to stop consuming the canceled person’s content. This is the root of the issue around cancel culture: too often we claim to have canceled someone without realizing the gravitas of that statement, or paying any attention to its repercussions. While many pledged to never support Charles again after the release of Westbrook’s video, his response video titled, “No More Lies,” in which he defends himself, has accumulated 47 million views, more than any other video he had posted in the six months prior.

The internet can be the swiftest judge of character, but fundamentally lacks the judgement to decide whether cancelling a celebrity is conducive to society’s overall goal of removing problematic celebrities from the public eye. “I think it’s popular because people want to feel like they are doing something,” said Saavi Banerjee (‘22). “It’s gratifying to see someone “canceled,” but it’s not useful in the bigger picture.” This is the paradoxical nature of cancel culture: the more we punish people for their varying levels of crime, the lesser the sentence becomes each time.

Maya Buckley is a junior and The Tower's Social Media Manager. When she is not crying about her latest chemistry quiz, she enjoys singing in Bishop’s...