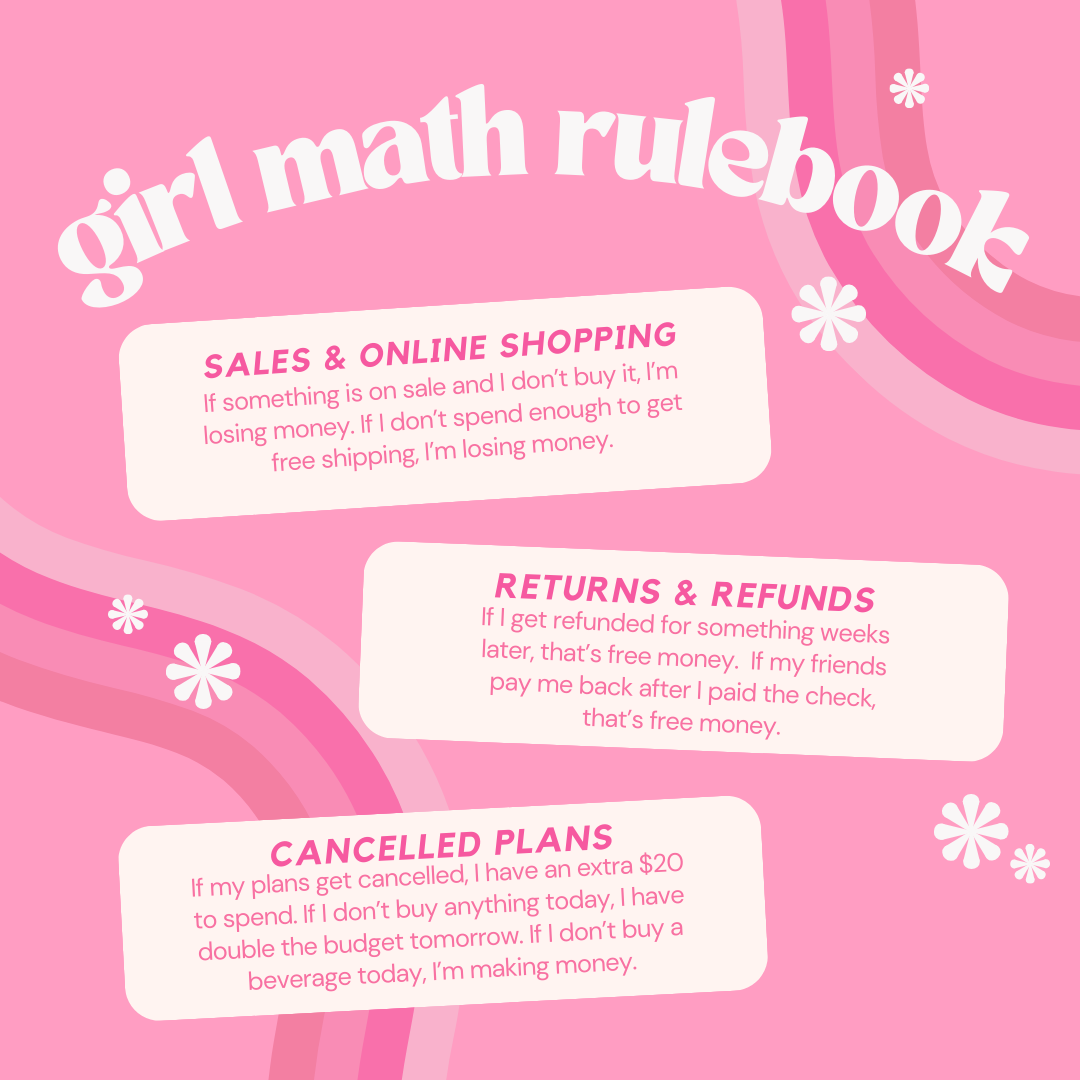

Did you know you’re losing money if you don’t spend enough to qualify for free shipping? You’re also making money whenever you skip your daily coffee; anything in your Venmo or Apple Wallet that isn’t immediately spent is free money, and anything under $5 is basically free.

These statements are true according to the “girl math” trend on TikTok that consists of women sharing their reasoning around spending money. The intent behind these TikToks seems to be to comfort those struggling to rationalize a purchase and also gently tease that justification. But “girl math” is just as misleading as it is beneficial.

The trend originated from the New Zealand podcast ZM where radio hosts Carl Fletch, Vaughan Smith, and Hayley Sproull answer calls from listeners sharing their recent expensive or unnecessary purchases. The hosts help them justify their spendings using “girl math.”

“I think we’ve all used girl math principles at one point or another to justify our decision making and to increase our personal utility,” Economics Teacher Mr. Damon Halback said. If this is true, then why are people calling it “girl math”?

Even though men and women have equal capabilities of intelligently spending their money, there is a stereotype that women are not as financially competent as men. “Girl math” may add to the stereotype in some ways, like how Serena Zhang (‘24) felt the need to prelude her statements with “I don’t have a spending problem; I don’t have a shopping addiction.”

In a sense, the trend is a showcase of self-examination: “I think it’s a way for us to be poking fun at [the stereotype that women are bad with money]. It’s self-awareness,” Serena said. Mr. Halback would argue “both [men and women] tend to make the same bad decisions, but women are more willing to accept that the decisions are bad than guys who feel more willing to justify that they’re bad.”

“I’m saddened that women would do this,” said Psychology and Economics Teacher Ms. Emily Smith, who thinks that supporting and posting “girl math” videos is problematic. Ms. Smith emphasized that the behaviors outlined in “girl math” are not limited to women. All humans rationalize their decisions to prevent feeling uncomfortable and irresponsible.

“Girl math” rationalizations are common. In Serena’s eyes, for example, a purchase with cash doesn’t “feel as significant because it doesn’t feel like it’s going to add up later,” unlike numbers dropping in a bank account.

Sofi Verma (‘24) uses many “girl math” principles and believes strongly in the idea that if she doesn’t buy something on sale, she is losing money. “I would buy it anyway,” she said. And by effect, she reasons she is saving money.

Loss aversion, when people are more sensitive to a loss than to a gain of the same amount, plays into this thinking. This is a human condition, and it doesn’t help that “every single company uses some form of marketing that takes advantage of the way in which we’re loss averse,” according to Mr. Halback.

Reasoning purchases with “girl math” certainly makes some people lack remorse that often comes with spending money. Sofi said, “It doesn’t make me feel guilty about spending money.”

To this point, Ms. Smith said, “From a psychological standpoint, if you can justify away your irrationality or your irresponsibility or whatever it is, that makes you feel better. It makes you less anxious.”

From an economic standpoint, Mr. Halback isn’t worried about the effects of “girl math” on anyone’s financial health. “There’s so much bad financial advice online. This is actually relatively harmless compared to other forms of bad financial advice,” he said.

“Girl math” principles “include what are clearly erroneous decisions, but they’re celebrating the fact that we do things that are not perfectly rational and that we’re humans and not econs,” Mr Halback said.

These principles, now masked under the name of “girl math,” are not new. “People have been doing this type of behavior for a long time. Now it’s taken a new name and it’s on social media,” Ms. Smith said.

As humans, Mr. Halback continued,“we spend all of our days making choices, and it’s just a way to celebrate the fact that we often make terrible choices but can have fun doing it.”