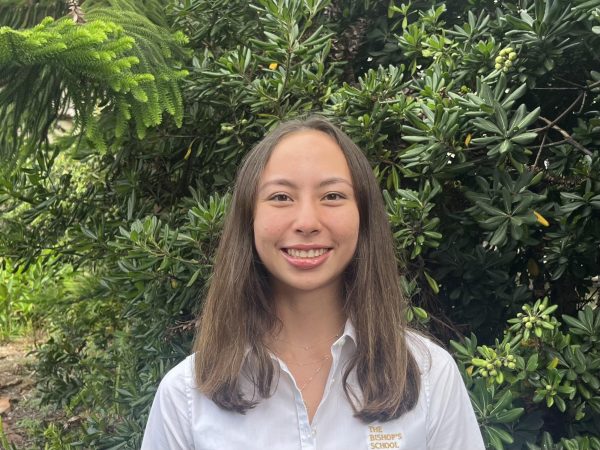

When Dartmouth deferred Sharisa You’s (‘22) Early Decision application, she questioned everything.

“I cried for, I don’t know, eight hours,” she said. “I kept thinking, what is wrong with me? What did I do wrong?” Over time, her mindset shifted. “Then you realize it’s not what you did. Since there’s so many applicants, you just have to have faith that everything will work out.” Sharisa is now a sophomore at Amherst College.

As competition increases and acceptance rates at top schools continue to plummet, more and more uncertainty surrounds the college application process. The ban on race-conscious admissions doesn’t help.

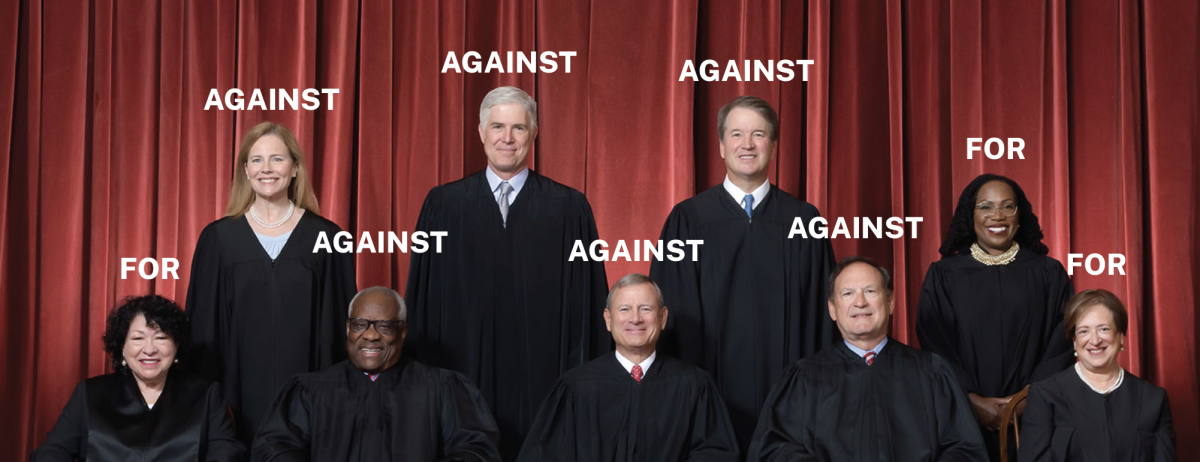

The facts

The Supreme Court struck down race-conscious college admissions in the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard case on June 29. The decision marks a historic change after decades of work towards racial equity in higher education.

Many universities released statements outlining an unwavering commitment to diversity. Harvard stated the school will “certainly comply with the Court’s decision,” and maintain the “fundamental principle that deep and transformative teaching, learning, and research depend upon a community comprising people of many backgrounds, perspectives, and lived experiences.” Stanford, Yale, Princeton, and countless other schools released similar statements.

Sarah Lawrence College even published a new supplemental essay prompt responding directly to the decision. The prompt asks applicants,“Drawing upon examples from your life, a quality of your character, and/or a unique ability you possess, describe how you believe your goals for a college education might be impacted, influenced, or affected by the Court’s decision.”

Although this change brings uncertainty, two of the country’s top public university systems have already seen the impact of banning race-conscious admissions.

The University of Michigan made the decision in 2006. According to the school’s published statistics, its Black student population decreased from 7 to 4 percent, and its Native American student population dropped from 1 to 0.11 percent. University of California (UC) schools discontinued race-conscious admissions in 1996, and the number of Black and Latino students at UCLA and UC Berkeley fell by 40 percent soon after the change went into effect, also according to the schools.

Both school systems continue to work to improve these statistics using strategies to view applicants holistically as well as expansive and costly outreach programs. The UC system, for example, has spent more than 500 million dollars since 2004 working to increase diversity among its students. Such efforts may not be possible for schools with less funding.

Effect on competition

Acceptance rates to top schools have already been decreasing for decades. Stanford, for example, accepted just 3.9 percent of the over 45,000 applications it received in 2022. In 2007, Stanford accepted 10.3 percent of the applicant pool, and in 1970, 22.4 percent. In 2007, the school had received nearly 24,000 applications, and in 1970, only 9,800. All the while, the school’s undergraduate population has remained between 6,200 and 6,700.

This trend, paralleled across the Ivy League and other top schools, is driven by students applying to a large number of schools.

Eric Chen (‘24) said everyone calls college admissions a lottery these days. “I hear that and I’m thinking, OK, well, if it is a lottery, I want to give myself as many chances as possible to win.”

Chen aims to apply to at least 15 schools this fall. Angeline Villachica (‘24) is aiming for around 20. Marcus Buu-Hoan (‘24), who plans to apply to “as many as possible,” affirmed, “It’s kind of becoming more of the norm.” College Counselor Ms. Marsha Setzer called it a “chicken-or-the-egg” phenomenon: with more competition, students will continue to apply to even more schools.

After Sharisa was deferred from Dartmouth, she expanded her college list and applied to 22 in the regular decision round. “It’s a psychological thing,” she said. “You feel like the more places you shoot your shot, the higher chances you have of getting in.” Of this strategy, Ms. Setzer said, “As it’s gotten harder and harder to predict outcomes, I can understand why students would choose to do that.”

The ever-changing machine of college admissions is poised to be even more unpredictable following the ban on race-conscious admissions, particularly for students in minority groups. “We’re going to try to predict as much as we possibly can,” College Counselor Ms. Noor Haddad said. “But this is unlike anything we’ve had in a really long time.”

Application changes

This level of uncertainty makes strategizing in applications more difficult. Marcus was already most unsure about how to describe himself in essays. “It’s a puzzle you have to solve where you choose the qualities you want to put forth, but also what you think the college would like to see,” he said.

Now, Marcus is faced with an additional decision whether to write about his ethnicity, a topic he was not planning to touch on before the Supreme Court ruling removed the “race” box from the Common App. As Vietnamese are an underrepresented minority, he wonders whether it may be helpful to mention this to schools that still value diversity.

Angeline Villachica (‘24), a first-generation student whose mom is from Mexico and dad is from Nicaragua, also grappled with including her identity in her essay. “It probably will be a part of my Common App essay,” she said. “If I didn’t have that, it would scare me a little bit in the sense of them not knowing all of my circumstances.”

Ms. Haddad and Ms. Setzer both emphasized authenticity in the application process. “I never want students to feel forced to write about something,” Ms. Haddad said. “I want a student to put together an application that highlights the things about themselves they want to put forward,” Ms. Setzer agreed.

Both described that their job is to assess students’ unique feelings and needs in the college process and tailor their support accordingly. They continued that the goal holds true for the many ways the ban on race-conscious admissions will affect students of different backgrounds.

After all, Bishop’s is an affluent school with abundant resources available to everyone. “I know I’m in a more privileged position because of the school I go to,” Angeline said of her reaction to the Supreme Court decision. “I was more upset for students who aren’t going to a private school, and don’t have as many resources.”