At Target, the weeks leading up to June began like any other. In honor of Pride month, the company put everything from rainbow cake mix to tuck-friendly swimsuits on display just as it had years prior — but unlike the preceding years, it removed some of its displays even before June began, mainly because of conservative backlash.

Following social media posts denouncing the company and destruction of some of the products by anti-LGBTQIA+ customers, Target said in a statement on May 24th, “Given these volatile circumstances, we are … removing items that have been at the center of the most significant confrontational behavior.”

This is just one of many instances of companies lending their support to a political or social movement, only to rescind their support when they face backlash. So why do companies take stances on issues if their opinions are subject to the whims of the consumer? And what are the benefits and drawbacks of this kind of support?

According to a 2020 issue of BU Today, Boston University’s daily newspaper, more than two-thirds of people want their brands to commit to social movements. In today’s climate of increased political polarization, people want to know what they are supporting and where their money is going. And sometimes, contrary to popular belief, taking a stand can actually help a company.

As Alina Selyukh, a business correspondent for NPR, said on the June 28th episode of Morning Edition, “a brand wants to connect with you on a deep level.” Marcus Collins, a marketing expert at the University of Michigan, added that when traditional messaging fails — “my razor’s sharper, my toothpaste has 25% more fluoride” — a social issue can make a brand a part of the consumer’s identity. He continued, saying “If my brand of ice cream tells me that we should dismantle white supremacy, you go, whoa, nelly,” and actually start to think about the issue it references. And if you support the issue, you feel that you should support the brand.

And this strategy can work, as it might result in more profit and customer loyalty. According to Economics Teacher Mr. Damon Halback, “In the case of Apple, as a creative ‘liberal’ brand, they are staying consistent with past corporate behavior. Apple has a huge customer base, but the stores, where a customer would interact with LGBTQ messaging, are all located in cosmopolitan areas.”

Because they are staying true to their long-held values and their stores are in areas that are less likely to dispute those values, Apple has successfully been able to navigate being a political company.

This becomes even more effective when brands have customer bases that lean the same way. It can increase brand loyalty and make people more comfortable in their decisions to purchase products from that company. For Patagonia, an outdoor clothing and equipment store, supporting environmental reform makes sense, because the people who shop there are likely to agree.

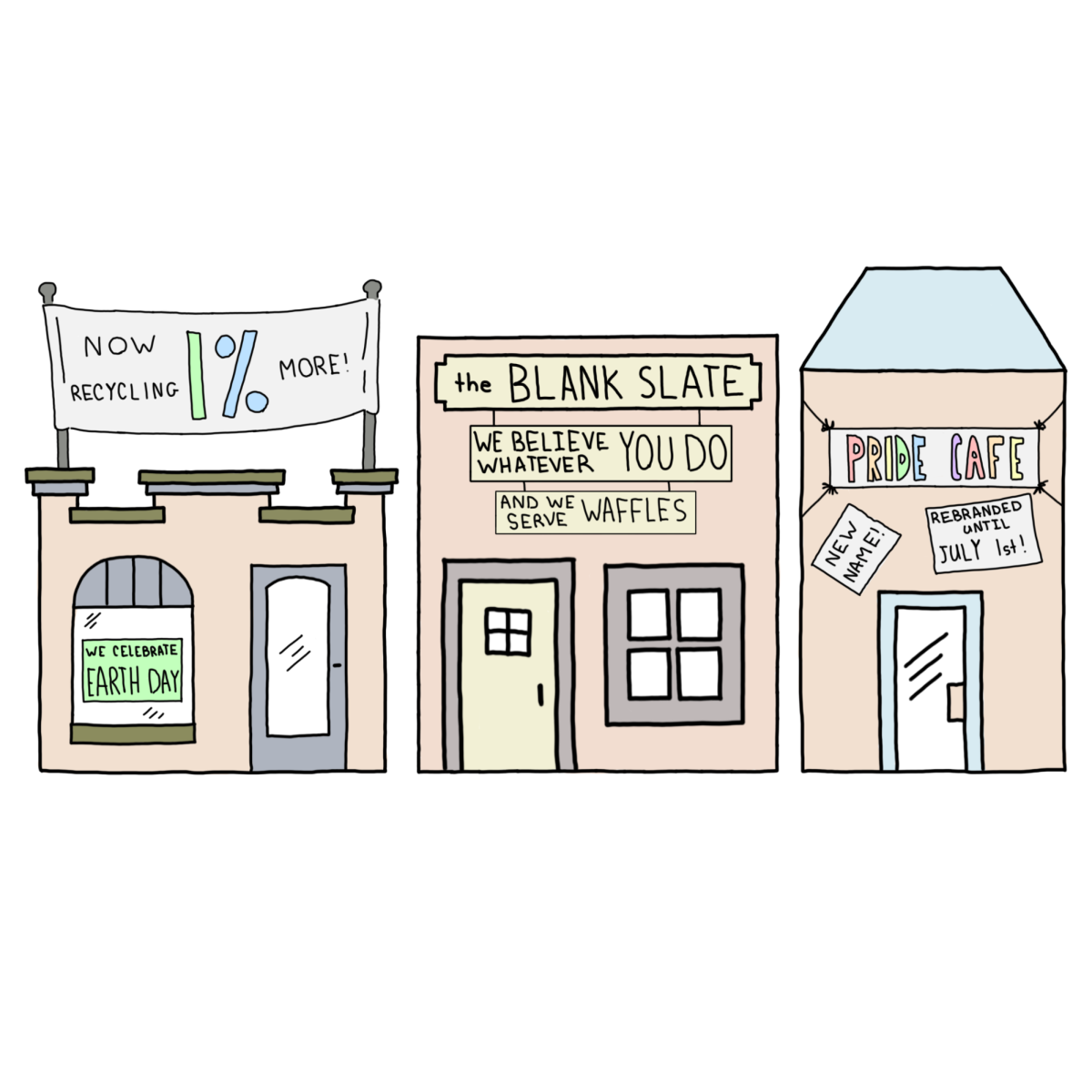

However, most companies have a mixed customer base, which can lead to backlash, regardless of what political or social issue they support. Take Target, for example: they attempted to appeal to their liberal and LGBTQIA+ customers with Pride merchandise but soon faced the anger of their conservative shoppers and had to remove the products.

But by making a statement and then rescinding it, Target — and many companies like it — might have unwittingly made their situation worse. By not totally committing to any one issue, companies alienate multiple groups of customers rather than just one.

As Mr. Collins put it, “not only did they lose the people that they originally pissed off or offended, but then they lost the people they had been supporting for years, all to play to this mythological middle.”

This trend, besides isolating potential buyers, can also make people question the sincerity of the companies. There is no doubt that companies pander to certain groups, attempting “to tap into the buying power of a group with growing financial, political and social clout,” according to Jordyn Holman and Julie Creswell of the New York Times. But when a brand voices its support only to take it away when faced with backlash, consumers begin to question whether it was ever about the politics or only about profit, which harms the companies and those who they said they were helping.

This is also the case when a brand lends its support to a social issue for only part of the year, rather than promoting it year-round, or engaging in performative activism. As Theo Cleary (‘24) of the Bishop’s Alliance of Queers and Non-Queers (BAQN) said, “Taking a public stance should be less about making some Pride soap or Juneteenth ice cream, and more like protecting people’s human rights within their companies.”

But even when brands are inclusive, even when they continuously promote an issue and their own values, it can still be difficult to ascertain the true motive; for some, that motive will always be profit. “A company is not an organization that is supposed to help people … a company is selling something and is trying to make a profit, that is the sole goal, and it’s inaccurate to say otherwise,” Theo said.

And while the goal of a company is to make money, some genuinely do want to help people. “There are companies that are owned by marginalized groups that want to help other people in that marginalized group,” said Theo. And according to Mr. Halback, “Corporate response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a significant factor in motivating political behavior.” Since “within a month of the invasion more than 350 significant American corporations had either left Russia altogether or suspended business for the duration of the invasion,” Russia’s ability to wage war was severely impacted.

But while we may never be able to truly ascertain the motives of a company promoting a social issue, we can continue to do our research and try to do what we think is best.