Scheduling: Debunked

A behind-the-scenes look at how schedules are put together

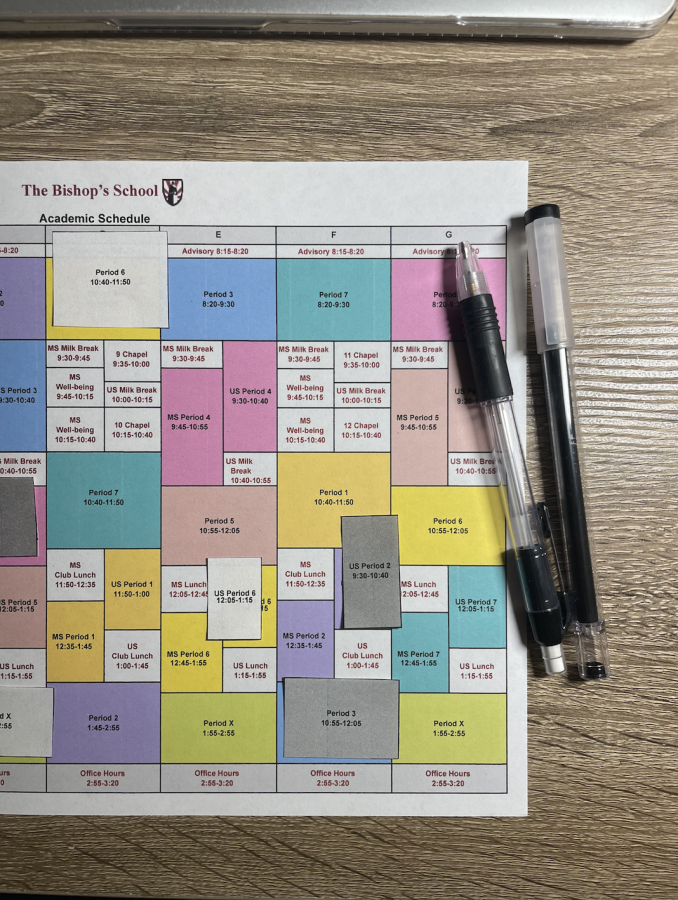

Putting together students’ schedules can be like a puzzle or sudoku-type game.

Every year, like clockwork, an email from Academic Dean Ms. Janice Murabayashi appears in our inboxes with a ding and a New email! notification. Students’ phones flood with texts from friends: “Schedules are out!” and just like that, the foundation of our academic lives for the next year is set–whether they got the classes they requested or, disastrously, did not. The behind-the-scenes work of putting these schedules together can be a mystery to students. “I had no idea how they manage to make everything work out for most of us,” Joseph Aguilar (‘22) said. So let’s pull back the curtain.

At Bishop’s, there isn’t a Wizard-of-Oz-like man sitting bumbling and alone behind the curtain. Rather, it’s a team of administrators and faculty who work on courses and scheduling, led largely by Ms. Murabayashi and our college counselors: Director of College Counseling Ms. Wendy Chang, Ms. Noor Haddad, Mr. AJ Jezierski, and Ms. Marsha Setzer.

“People play different roles at different times in the process,” Ms. Murabayashi said. For example, she continued, Academic Assistant to Head of Upper School Ms. Marianne Kullback and Registrar Ms. Rachael Garcia contribute greatly to the early days before a given school year ends, sifting through course recommendations from teachers and making the course catalog accessible to students.

Once all our course requests are received, the scheduling program—affectionately called “The Matrix” by the college counseling—comes into play. “The computer builds the matrix and then a human being goes through and looks at it. That’s what we call it—the Matrix,” Ms. Setzer said laughingly.

According to Ms. Murabayashi, it needs to be told what courses are being offered and how many sections of each there should be. “We’re very student-driven from year to year,” she said, “so we don’t just say there’s only going to be one period of [a certain class]: we see what the requests are.” This means there may be four sections of Honors Euro one year and three the next, if rising sophomores of the next grade are, for whatever reason, less drawn to European History. This year, for example, saw an unprecedented number of students sign up for Honors Psychology, leading to the splitting of six sections between History and Social Sciences teachers Mrs. Emily Smith and Ms. Karri Woods. The exceptions to this rule are some advanced classes that require applications–say, Honors Writing or Honors U.S. Government and Politics (Mock Trial)–and electives like Journalism or Bishop’s Singers. These aren’t able to be split into multiple sections at all.

“Once we have [the data] cleaned up and set up, I ‘push the button,’ and what the program tries to do is get as many students into as many classes as it can,” Ms. Murabayashi said.

From there follow several iterations of this “button-pushing” where the Matrix attempts to populate as many students into as many requested classes as it can, keeping in mind evenness of class size and gender balance in sections, Ms. Murabayashi said. And, of course, graduation requirements are prioritized. After any given round, the team will comb through the computer’s output and manually switch around a period or two to try to get matches for the greatest possible number of students and the least number of conflicts.

“You may not feel like this, but there is a lot of work done on the back end to avoid as many of those conflicts as possible,” Ms. Setzer said. “It’s impossible to offer every class in every period, so decisions have to be made to put classes in certain periods.”

With the most widely-offered, grade-level classes, scheduling conflicts are fewer and far between since there’s usually numerous sections of, say, Precalculus or Honors Biology, which are both classes taken by the majority of juniors. Trouble with conflicts most often arises with, naturally, the classes that are only offered one period, like those electives or higher-level courses requiring prerequisites or applications.

“Any class that has multiple grades in it, it’s never going to find one period that works for everyone,” Ms. Murabayashi said, “So, there’s always going to be somebody who’s kind of left out, which is a bummer, but that’s the tricky thing about a single class that has four grades in its span.”

Joseph was faced with one such scheduling dilemma at the beginning of this school year, when he found out he wouldn’t be able to enroll in Acting Workshop or Bishop’s Singers, two high-level arts extracurriculars that he’d been partaking in for years. “It was a bummer, at first,” he said. “I was looking forward to all the senior projects, to being a senior in those classes and getting the privileges of doing that, and then it didn’t pan out because of scheduling gods and luck.”

He did learn to make the best of it, taking part in choir when he can and beginning an Independent Study in directing with Performing Arts teacher Ms. Samantha Howard. “I’m learning more about directing and I’m going to be able to direct my own show at the end of the year, and I don’t think I would’ve been able to do that if I’d been in [Acting Workshop] from the start,” he said. “I’m partially bummed about it, but I’m partially thankful that it happened.”

Acting Workshop is one of those tricky classes that are only offered one period, all dubbed ‘singletons’ by Ms. Murabayashi. “From what I’ve seen, [conflicts] also ends up mostly being kids who take performing arts classes, because most are singletons,” corroborated Sophia Gleeson (‘24), who was admitted to the School’s most advanced dance class, Performing Dance Group, but wasn’t able to take the class due to a conflict with a chemistry lab.

When a situation like Joseph’s arises, Ms. Murabayashi and our college counselors work closely with students to try for the best possible outcome. “When a student has a conflict, I find it important to be upfront in explaining what the situation actually is,” Mr. Jezierski told The Tower. “If it is course X vs. course Y, and there is no way to fit both, the student will have to make a choice. Sometimes, other things can be moved around to make everything fit, but this isn’t always the case.”

According to Ms. Murabayashi, as students move up in grade level and more electives or advanced courses become available to them, the more mentally prepared they should be for a conflict. “The great thing is that you get more opportunities, and as a result of those opportunities, you also have to make more choices,” she said. Such is the great burden of the Bishop’s high schooler.

Sariah Hossain is a senior and The Tower's Co-Editor-in-Chief. This is her fourth year on the publication and, as her friends can all attest, writing...